Designing an HVAC system for a biosafety laboratory is a high-stakes engineering challenge where a single design flaw can compromise containment. The core problem isn’t just selecting equipment; it’s integrating pressure cascades, airflow direction, and filtration into a fail-safe system that performs under both normal and failure conditions. Professionals must navigate a complex landscape of standards, from the foundational principles of the BMBL to the rigorous testing protocols of ANSI/ASSP Z9.14, while balancing performance with practical maintenance and validation.

The urgency for precise design has intensified with the expansion of high-containment research in pharmaceuticals, public health, and emerging pathogen studies. Regulatory scrutiny is higher than ever, and the cost of non-compliance—whether in failed certification, research downtime, or safety incidents—is prohibitive. A compliant HVAC system is the engineered backbone of laboratory safety, requiring a methodical approach from risk assessment through to predictive maintenance.

Pressure Cascade Design: Core Principles for BSL 2, 3, and 4

Defining the Pressure Hierarchy

The pressure cascade is not about creating a vacuum but establishing a controlled, relative gradient of negative pressure. This gradient ensures air flows from clean areas (corridors) to potentially contaminated spaces (the lab), preventing the escape of aerosols. The goal is to maintain a minimum differential, typically starting at 0.05 inches of water gauge (W.G.), with design often targeting 0.06″ W.G. for improved stability and monitorability. This subtle but critical difference defines the containment boundary.

Engineering for Cascade Integrity

Achieving a stable cascade requires more than just fan control. The entire building envelope within the containment zone must be meticulously sealed. Gaps in interstitial spaces—above ceilings, behind walls, and around penetrations—can collapse the pressure differential, rendering the cascade ineffective. Industry experts recommend treating the lab as a sealed vessel; the HVAC system then actively creates and controls the internal pressure condition relative to surrounding spaces. This holistic view of architecture and mechanical systems is non-negotiable.

Application Across Biosafety Levels

The stringency of cascade design escalates with risk. A BSL-2 lab may function with general lab ventilation, while BSL-3 mandates a defined, monitorable cascade (e.g., corridor to anteroom to main lab). BSL-4 requires the highest level of control and redundancy. The table below illustrates a typical pressure zoning strategy for a BSL-3 containment suite.

| Pressure Zone | Typical Pressure Differential | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Corridor (Reference) | 0.00″ W.G. | Least negative zone |

| Anteroom | -0.05″ to -0.06″ W.G. | Intermediate buffer zone |

| Main Lab (BSL-3) | -0.06″ to -0.10″ W.G. | Most negative, inward airflow |

Source: CDC/NIH Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories (BMBL), 6th Edition. The BMBL establishes the foundational requirement for directional inward airflow and negative pressure differentials to contain hazardous agents, which is the core principle behind pressure cascade design.

Air Change Rates (ACH): Standards for Each Biosafety Level

The Dual Role of ACH

Air Change per Hour (ACH) rates serve two primary functions: contaminant dilution and environmental control. Sufficient air changes reduce the concentration of airborne particles, while the associated airflow facilitates temperature and humidity management. Standards like ANSI/ASHRAE/ASHE Standard 170-2021 provide a critical framework, offering validated ranges for spaces requiring infection control, which directly inform lab design.

Specific Requirements by Zone

ACH requirements are not uniform across a facility. They are strategically tiered to match the risk profile of each zone. Corridors require minimal dilution (6-8 ACH), anterooms need higher flushing rates (10-12 ACH) to maintain the buffer, and the main BSL-3 lab requires the highest rate (12-15 ACH) for effective containment. For BSL-3 and above, a fundamental constraint is the prohibition of air recirculation; 100% of exhaust must be once-through and externally discharged after HEPA filtration.

Integrating Climate Control

The volume of air required for ACH directly impacts the HVAC system’s ability to maintain precise environmental conditions. Temperature (65-72°F) and humidity (35-55% RH) must be tightly controlled for personnel comfort and to prevent conditions that could compromise experiments or containment integrity—such as condensation on surfaces. Humidification often requires clean steam injection to avoid introducing contaminants. The following table outlines key parameters.

| Space / Level | Air Changes Per Hour (ACH) | Key Constraint |

|---|---|---|

| Corridors (General) | 6 – 8 ACH | Minimum dilution ventilation |

| Anterooms (BSL-3) | 10 – 12 ACH | Buffer zone air flushing |

| BSL-3 Laboratory | 12 – 15 ACH | 100% once-through air |

| Temperature Control | 65 – 72 °F | Personnel comfort & stability |

| Humidity Control | 35 – 55 % RH | Prevents condensation, static |

Source: ANSI/ASHRAE/ASHE Standard 170-2021. While focused on healthcare, this standard provides authoritative ventilation and environmental parameter ranges critical for infection control, which directly informs ACH and climate design for containment labs.

Directional Airflow: Engineering for Fail-Safe Containment

Beyond Steady-State Design

Directional airflow must be maintainable under all operating conditions, especially during system failures. This mandates dedicated, independent HVAC systems for BSL-3/4 labs, with each containment room served by its own air terminals. The design imperative shifts from optimizing steady-state performance to ensuring graceful degradation. Systems must anticipate and manage cascading failures, such as a primary exhaust fan loss, without allowing a reversal of airflow at the containment boundary.

Fail-Safe Controls and Dampers

Achieving fail-safe operation requires specific control sequences for dampers and fans. Upon detecting a fault, control logic must default actuators to a position that preserves inward airflow. For example, backdraft dampers on exhaust must fail closed, and supply air dampers may need to modulate closed to maintain room negative pressure. These sequences are not generic; they must be custom-designed for the specific system architecture and validated through simulated failure testing.

Validating Failure Mode Performance

The true test of directional airflow design occurs during simulated fault conditions. Testing per ANSI/ASSP Z9.14-2020 involves manually failing primary components (e.g., turning off an exhaust fan) and verifying that backup systems engage and that inward airflow is maintained at all room barriers, typically using smoke tubes. This holistic validation proves the system’s resilience and is a required step for certification.

HEPA Filtration & Redundancy: Critical System Safeguards

Terminal Placement and Material Specifications

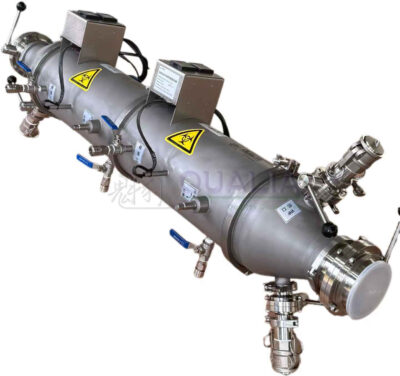

HEPA filtration is the final barrier for exhaust air and often the first for supply air entering containment. Terminal placement—as close as possible to the room barrier—is critical to minimize contaminated ductwork. A frequently overlooked detail involves the ductwork downstream of in-duct HEPA filters. This duct must be constructed of non-shedding materials like anodized aluminum or stainless steel to prevent introducing particulate contamination after the filter, a specification that extends containment philosophy into the mechanical infrastructure.

Implementing Redundant Systems

Redundancy is engineered to prevent a single point of failure from breaching containment. This typically involves an N+1 configuration for exhaust fans, where one fan can fail without dropping the system below required airflow. Additionally, automatic transfer switches to emergency power (generator or UPS) are mandatory to maintain fan operation during a power outage. This layered approach ensures system uptime and safety.

Component Requirements and Rationale

Each component in the filtration and exhaust chain has a specific role in safeguarding containment. The table below summarizes these critical requirements.

| Component | Key Requirement | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Exhaust HEPA | Terminal, at barrier | Final containment safeguard |

| Supply HEPA | Typically required | Protects lab interior |

| Downstream Duct | Non-shedding material (e.g., stainless) | Prevents post-filter contamination |

| Exhaust Fans | N+1 Redundant configuration | Ensures system uptime |

| Power Supply | Automatic emergency transfer | Maintains airflow during outage |

Source: CDC/NIH Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories (BMBL), 6th Edition. The BMBL mandates HEPA filtration of exhaust air for BSL-3 and BSL-4 and emphasizes the need for reliable ventilation system operation, forming the basis for redundancy requirements.

Integrating HVAC with Biological Safety Cabinets (BSCs)

Balancing Primary and Secondary Containment

The laboratory’s secondary containment (room HVAC) must not conflict with its primary containment devices (BSCs). Hard-ducted Class II Type B2 cabinets, which exhaust 100% of their airflow, become integral components of the room’s exhaust system. Their operation must be interlocked with the room HVAC controls to maintain overall air balance. A failure to coordinate can result in pressure reversals at the BSC face or room doors, compromising safety.

Managing Complex Pressure Zones

Integration creates complex pressure dynamics, particularly in transition spaces like gowning rooms. These rooms may need to be positive relative to a non-lab corridor but still negative relative to the main lab, creating a multi-step pressure cascade. Engineering these intermediary spaces requires precise airflow calculations to ensure both personnel protection (during gowning/degowning) and overall containment integrity are maintained.

Connection Strategies: Hard-Duct vs. Thimble

The choice between hard-ducting a BSC or using a canopy/thimble connection involves trade-offs. Hard-ducting offers a direct, sealed connection but reduces cabinet mobility and requires careful static pressure control. Thimble connections allow for cabinet removal but rely on maintaining a specific airflow capture velocity at the thimble opening to contain exhaust. The selection impacts overall system design, flexibility, and testing protocols.

Validation & Testing: Protocols for Performance Verification

The Mandate of ANSI/ASSP Z9.14

The ANSI/ASSP Z9.14-2020 standard was created specifically to provide rigorous, repeatable methodologies for testing BSL-3/4 ventilation systems. It moves beyond the performance objectives outlined in the BMBL to prescribe exact test procedures, frequencies, and acceptance criteria. Adherence to this standard is now considered a best practice and is often required by facility certifying bodies.

Testing Regime: Initial, Annual, and Event-Driven

Performance verification is not a one-time event. It begins with initial commissioning and continues with annual recertification. Crucially, testing is also event-driven; any modification to the HVAC system—a fan replacement, control sequence update, or ductwork alteration—triggers a requirement for full re-verification. This places a reactive budgeting and planning burden on facility owners that must be anticipated.

Key Tests and Performance Indicators

The validation protocol encompasses a suite of tests designed to prove both normal and failure-mode operation. The following table outlines the core components of this regime.

| Test Type | Frequency / Trigger | Key Performance Indicator |

|---|---|---|

| Sensor Calibration | Initial & Annual | Measurement accuracy |

| Airflow Measurement | Initial & Annual | Meets designed ACH, pressure |

| Failure Mode Testing | Annual & Post-modification | No airflow reversal |

| Boundary Integrity | Smoke tube testing | Inward airflow at barriers |

| Data Review | Continuous (BAS trends) | System performance logging |

Source: ANSI/ASSP Z9.14-2020. This standard provides the specific methodologies for testing and performance verification of BSL-3/4 ventilation systems, mandating the tests and frequencies listed to ensure containment safety.

Key Differences in HVAC Requirements: BSL-2 vs. BSL-3 vs. BSL-4

A Progressive Risk-Based Framework

HVAC requirements escalate in a logical, risk-based progression defined by the CDC/NIH Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories (BMBL), 6th Edition. BSL-2 handles agents of moderate risk, BSL-3 addresses indigenous or exotic agents with potential for aerosol transmission, and BSL-4 is for dangerous/exotic agents posing high individual risk of life-threatening disease. The engineering controls are calibrated to this rising risk profile.

Comparing Core Engineering Controls

The differences manifest in system dedication, air handling philosophy, filtration, and control complexity. BSL-2 may use general ventilation with possible local exhaust, while BSL-3 mandates a dedicated, 100% once-through system. BSL-4 incorporates all BSL-3 controls and adds further layers, such as effluent decontamination and often double HEPA exhaust filters in series. The regulatory approval pathway also lengthens and intensifies significantly with each level.

Decision Framework for Facility Planning

Understanding these distinctions is crucial for early-stage planning and budgeting. The table below provides a clear, side-by-side comparison to inform feasibility studies and design charrettes.

| Requirement | BSL-2 | BSL-3 | BSL-4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| System Dedication | General lab ventilation possible | Dedicated system mandatory | Dedicated, enhanced redundancy |

| Air Recirculation | May be permitted | 100% once-through air | 100% once-through air |

| Exhaust Filtration | Local exhaust possible | Terminal HEPA required | Double HEPA (in series) often |

| Pressure Cascade | May not be required | Stringent cascade required | Maximum stringency & monitoring |

| Regulatory Scrutiny | Moderate | High | Very High / External review |

Source: CDC/NIH Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories (BMBL), 6th Edition. The BMBL outlines the progressive, risk-based containment principles that define the escalating HVAC engineering controls required for each biosafety level.

Implementing a Compliant BSL HVAC System: A Step-by-Step Guide

Phase 1: Risk Assessment and Standard Selection

Success begins with a clear risk assessment to define the required Biosafety Level and select the governing standards. The BMBL provides the risk principles, while ANSI/ASSP Z9.14 defines the verification methodology. For new construction, a greenfield site often presents fewer hidden challenges than retrofitting an existing facility, where structural or spatial constraints can invalidate theoretical designs.

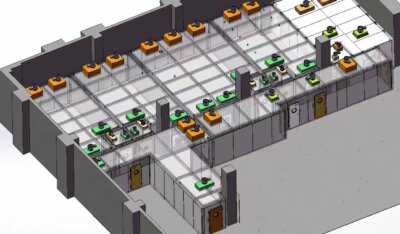

Phase 2: Design and Specification

The design phase must prioritize sealing the building envelope. Specifications must detail non-shedding materials for ductwork, terminal HEPA filter housings with test ports, and a robust Building Automation System (BAS) for continuous monitoring and alarm annunciation. The rise of prefabricated modular labs introduces pre-engineered, compact HVAC solutions for containment laboratories, shifting the focus to evaluating lifecycle maintenance access and integration with the site-built infrastructure.

Phase 3: Commissioning and Predictive Maintenance

Commissioning is the beginning of the operational lifecycle, not the end. The data collected during performance verification establishes a baseline. A forward-looking approach leverages this BAS trend data, applying analytics and AI-driven pattern recognition to shift from reactive repairs to predictive maintenance. This proactive stance anticipates component degradation before it triggers an alarm or fails a test, ensuring continuous compliance and operational resilience.

A compliant BSL HVAC system is defined by its validated performance under failure, not its design specifications on paper. The core decision points involve selecting the correct standards from the outset, designing for failure-mode integrity, and committing to a lifecycle of rigorous verification and predictive maintenance. The complexity of integrating pressure cascades, directional airflow, and redundant filtration demands a holistic engineering approach from concept through to decommissioning.

Need professional guidance on designing or validating a high-containment HVAC system? The experts at QUALIA specialize in the integration of critical engineering controls for biosafety facilities, ensuring designs meet stringent standards and perform reliably. Contact us to discuss your project requirements and navigate the path to certification.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What is the minimum pressure differential required for a BSL containment cascade, and how is it maintained?

A: A minimum relative pressure differential of 0.05 inches of water gauge (W.G.) is standard, with 0.06″ W.G. often specified for more robust control. This gradient, flowing from less negative corridors to the most negative lab space, requires all interstitial spaces like walls and ceilings to be completely sealed to prevent the cascade from collapsing. This means your design and construction teams must prioritize airtight building envelope details as much as the mechanical system specifications to ensure containment integrity.

Q: How do air change rate (ACH) requirements differ between BSL-2 and BSL-3 laboratories?

A: BSL-2 labs may use general ventilation with possible local exhaust and can sometimes recirculate air within the room. In contrast, BSL-3 facilities mandate dedicated, 100% once-through air systems with no recirculation, and typical design ranges for the lab space are 12-15 ACH. This fundamental shift means BSL-3 projects require significantly larger HVAC equipment, more energy for conditioning fresh air, and exhaust systems capable of handling the full air volume, directly impacting capital and operational costs.

Q: What is the critical failure mode we must test for in BSL-3/4 directional airflow systems?

A: The paramount test is verifying no airflow reversal occurs at the containment boundary during a system failure, such as a primary fan loss. This requires simulating fault conditions to prove that backup systems and damper sequences default to a containment-safe state, preserving inward airflow. According to ANSI/ASSP Z9.14-2020, your commissioning plan must include these failure scenario tests, meaning you need to budget for more complex and time-consuming performance verification.

Q: Why is ductwork material specification critical downstream of in-duct HEPA filters?

A: When HEPA filters are placed within the ductwork, all downstream components must be constructed of non-shedding materials like anodized aluminum or stainless steel. This prevents the duct itself from becoming a source of contamination after the filtration point. For your project, this extends material and fabrication requirements deep into the mechanical infrastructure, influencing cost and requiring strict oversight during installation to maintain the clean pathway.

Q: How does integrating a hard-ducted BSC complicate the room’s HVAC pressure balance?

A: A hard-ducted Biological Safety Cabinet, such as a Class II Type B2, becomes an integral part of the lab’s exhaust system. Its operation directly affects the room’s air volume and must be carefully interlocked with the main HVAC controls to maintain the overall pressure cascade. This means your control strategy must dynamically account for the BSC’s operational states, requiring more sophisticated Building Automation System (BAS) programming and integrated testing to ensure stability.

Q: What triggers a requirement for full re-verification of a BSL-3 HVAC system?

A: Any major modification, including fan replacement, control logic updates, or significant ductwork changes, mandates a complete system re-verification per standards like ANSI/ASSP Z9.14-2020. This obligation is continuous and event-triggered, not just annual. For facility owners, this demands proactive reactive budgeting and planning, as even well-intentioned upgrades or repairs can incur substantial additional validation costs and downtime.

Q: What are the key HVAC differentiators when planning a BSL-4 facility versus a BSL-3?

A: BSL-4 incorporates all BSL-3 mandates—dedicated 100% exhaust, stringent cascades, and failure testing—and adds further layers of protection. This typically includes double HEPA exhaust filters in series and often complex effluent decontamination systems for the exhaust air stream. This progression means BSL-4 projects face exponentially greater design complexity, higher equipment redundancy, and the most intense level of regulatory review, fundamentally altering project timelines and approval processes.

Related Contents:

- How to Calculate HVAC Air Changes Per Hour (ACH) Requirements for Modular BSL-2 and BSL-3 Laboratories

- BSL-4 Pressure Cascades: Advanced System Design

- BSL-3 Lab Ventilation: Design for Optimal Safety

- BSL-4 Air Handling: Critical System Requirements

- Installing Modular BSL-3 Labs: Expert Guide

- BSL-3 Air Handling: Critical Unit Requirements

- Air Handling in BSL-3 vs BSL-4: System Comparison

- Biosafety Cabinet Exhaust Systems Explained

- BSL-4 Lab Airflow Control: Ensuring Biosafety