Designing a negative pressure cascade for a BSL-3 laboratory is a high-stakes engineering challenge. The core problem is not just achieving a pressure differential but creating a resilient, multi-layered containment envelope that functions as a unified system. A common misconception is viewing the HVAC system in isolation from primary containment devices and operational protocols. The true challenge lies in integrating these components into a fail-safe architecture where mechanical reliability is synonymous with biosafety.

Attention to this design discipline is critical now due to expanding global research into high-consequence pathogens and increased regulatory scrutiny. A poorly designed or maintained pressure cascade represents a catastrophic single point of failure. The system must perform flawlessly during normal operations, equipment failure, and personnel movement, all while enabling rigorous decontamination cycles. This demands a design philosophy that prioritizes verified performance over mere specification compliance.

Core Principles of a BSL-3 Negative Pressure Cascade

Defining the Pressure Gradient

The foundational engineering control is a unidirectional airflow gradient, established by creating a series of zones at progressively lower pressures. A typical cascade flows from a corridor through an airlock and gowning area into the main laboratory, and finally into primary containment devices. This principle is not a single-system function but a layered defense, where the integrity of each pressure zone is essential to prevent pathogen escape. The minimum differential of -12.5 Pa between the lab and adjacent areas is a regulatory floor, not a design target.

The Airlock as an Engineered Subsystem

The airlock is not merely a door but a critical pressure transition zone. It must actively maintain cascade integrity during personnel ingress and egress, preventing pressure equalization. This often involves interlocked doors and a dedicated exhaust to sustain the gradient. Industry experts recommend designing this subsystem with its own monitoring and control logic, treating it as a vital component rather than an architectural afterthought. Its failure can compromise the entire containment envelope.

Quantifying the Safety Margin

Many facilities design for a target of -25 Pa to provide a critical safety margin. This buffer accounts for system disturbances like door openings, sash movements on biosafety cabinets, and filter loading. We compared facilities operating at the minimum versus those with a designed margin and found the latter experienced fewer alarm events and maintained containment during minor upsets. The following table outlines the key pressure relationships in a standard cascade.

Pressure Zone Specifications

This table defines the critical pressure differentials and functions for each zone in a BSL-3 containment cascade, based on authoritative guidelines.

| Pressure Zone | Minimum Differential Pressure | Key Function |

|---|---|---|

| Laboratory to adjacent area | -12.5 Pa (-0.05″ w.g.) | Minimum containment gradient |

| Typical design target | -25 Pa | Critical safety margin |

| Airlock / Gowning area | Progressive gradient | Engineered pressure transition |

| Biosafety Cabinet (BSC) | Lowest pressure | Primary containment device |

Source: CDC/NIH Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories (BMBL) 6th Edition. Appendix E authoritatively outlines the requirement for directional airflow (negative pressure) and establishes the foundational principle of a pressure cascade for BSL-3 containment.

Key HVAC Design Requirements for BSL-3 Containment

Mandatory Airflow and Filtration

BSL-3 HVAC systems must be dedicated and provide 100% once-through, non-recirculated airflow. All exhaust is HEPA-filtered before discharge. HEPA filtration serves a dual containment and protection role, acting as a two-way barrier. This necessitates bag-in/bag-out housings for safe filter change-out. The system’s reliability directly dictates containment safety, making redundancy non-negotiable.

Establishing Air Change Rates

Air change rates are a minimum of 6-12 ACH, with 10-12 ACH often specified. Higher rates enhance containment dilution and reduce decontamination cycle times for fumigation. Easily overlooked details include ensuring supply diffuser and exhaust grille placement supports uniform air mixing without creating dead zones that could harbor contaminants. Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) modeling is essential here.

System Specifications and Redundancy

The capital-intensive nature of these systems stems from the need for absolute reliability. N+1 redundancy for critical fans and connection to emergency power is standard. A single point of failure is unacceptable. The technical specifications form the backbone of the secondary containment strategy.

| Parameter | Requirement | Critical Component |

|---|---|---|

| Airflow type | 100% once-through, non-recirculated | Dedicated supply & exhaust |

| Minimum Air Change Rate (ACH) | 6-12 ACH | Ventilation for containment |

| Typical operational ACH | 10-12 ACH | Enhanced containment & decontamination |

| Exhaust filtration | HEPA (99.97% @ 0.3µm) | Two-way environmental barrier |

| Filter housing | Bag-in/bag-out | Safe change-out procedure |

| System redundancy | N+1 for critical fans | Emergency power connection |

Source: CDC/NIH Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories (BMBL) 6th Edition. The BMBL specifies requirements for dedicated ventilation, HEPA filtration of exhaust, and minimum air change rates, forming the core technical specifications for BSL-3 secondary containment.

Technical Mechanisms for Pressure Control and Monitoring

Active Pressure Control Hardware

Pressure control is actively managed by modulating the relationship between supply and exhaust airflows. Dynamically controlled venturi valves or dampers respond to disturbances within seconds. These components must have a proven track record in critical environments. Their selection impacts the system’s responsiveness to everyday events like door openings.

Integrated Digital Monitoring

This hardware integrates with a Building Management System (BMS) for continuous, real-time monitoring of differentials, airflow, and filter status. This integrated digital monitoring forms the facility’s central nervous system, enabling predictive maintenance. Alarms must be tiered, distinguishing between immediate containment breaches and maintenance advisories. In my experience, a well-configured BMS is the most powerful tool for operational assurance and audit compliance.

Proactive Risk Mitigation with CFD

Proactive CFD modeling is a strategic risk mitigation tool. It simulates failure scenarios like fan loss or duct breach to validate containment efficacy before construction. This moves design beyond compliance to performance-verified outcomes. The table below summarizes the key components of this control and monitoring ecosystem.

| System Component | Primary Function | Performance Metric |

|---|---|---|

| Venturi valves / Dampers | Modulate supply/exhaust flow | Respond within seconds |

| Building Management System (BMS) | Continuous real-time monitoring | Centralized alarm triggering |

| Pressure sensors | Monitor differentials | Detect < -12.5 Pa deviations |

| Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) | Simulate failure scenarios | Pre-construction risk mitigation |

Source: [ANSI/ASSP Z9.14-2021 Testing and Performance Verification Methodologies for Biosafety Level 3 (BSL-3) and Animal Biosafety Level 3 (ABSL-3) HVAC Systems]. This standard provides methodologies for verifying the performance of active pressure control systems and integrated monitoring, ensuring they meet design and safety intent.

Integrating Primary Containment with Room HVAC Systems

The Interdependence Challenge

The room HVAC must be seamlessly coordinated with primary containment equipment. A hard-ducted Class II Type B2 biosafety cabinet becomes an integral part of the exhaust stream. The room’s exhaust design must accommodate the BSC’s flow without disrupting the overall room pressure balance. This integration is complex; the performance of primary devices is interdependent with the room’s secondary containment envelope.

Modeling for Integration

This integration benefits from advanced planning with CFD analysis to model airflow patterns under normal and failure conditions. It reveals how a BSC exhaust fan failure might affect room pressure. This analysis is crucial for selecting appropriate control sequences and damper arrangements. It underscores why retrofitting older labs is a major, complex undertaking, often involving challenging integration of new equipment with legacy infrastructure.

A Holistic System View

The strategic implication is that containment is a holistic system. Specifications for biosafety cabinets must include their interaction parameters with the room HVAC. Commissioning must test the integrated performance, not just individual components. This holistic view is essential for achieving reliable advanced containment system design.

Essential Redundancy and Fail-Safe Design Strategies

The Philosophy of Layered Redundancy

Redundancy is a non-negotiable design philosophy. It extends beyond N+1 fans to include Uninterruptible Power Supplies (UPS), emergency generators, redundant sensors, and control processors with automatic failover logic. These capital-intensive requirements are a direct operational implication of the principle that system reliability equals containment safety.

Designing for Fail-Safe Outcomes

The system must be designed to fail safely. A fan failure should not cause a pressure reversal. This often involves specific damper configurations that close upon loss of power to maintain directional airflow. Control logic must default to a safe state. For the highest-risk applications, double HEPA filtration in series on the exhaust may be employed.

Redundancy Tier Implementation

Implementing these strategies requires a clear mapping of redundancy tiers to failure modes. The following framework outlines common approaches.

| Redundancy Tier | Component Examples | Fail-Safe Design Logic |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanical (N+1) | Exhaust fans, supply fans | Automatic backup activation |

| Power | UPS, Emergency generators | Maintains differential pressure |

| Control | Sensors, processors | Automatic failover logic |

| Filtration | Double HEPA in series | Highest-risk applications |

| Dampers | Specific configurations | Close on power loss |

Source: Technical documentation and industry specifications.

Commissioning, Validation, and Ongoing Certification

The Commissioning Imperative

Before operational use, the complete system must undergo rigorous commissioning. This process verifies that design intent translates to operational reality. It includes physical verification of pressure differentials, smoke testing for airflow visualization, and HEPA filter integrity testing. This is a legal and safety imperative, not an optional final step.

Mandatory Testing Protocols

Full alarm and failure-mode response testing are critical. Simulating faults validates both the hardware response and the operational team’s procedures. Lifecycle cost models must include these recurring certification expenses. Operational schedules must accommodate the necessary downtime to maintain regulatory compliance and insurance validity.

The Certification Cycle

The activities below are not one-time events but part of a recurring certification cycle mandated by standards like ANSI/ASSP Z9.14-2021.

| Activity | Method / Test | Required Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Pressure differential verification | Physical manometer reading | At commissioning & annually |

| Airflow visualization | Smoke testing | At commissioning |

| HEPA filter integrity test | DOP/PAO aerosol challenge | At commissioning & annually |

| Alarm & failure-mode testing | Simulated fault conditions | At commissioning & annually |

Source: [ANSI/ASSP Z9.14-2021 Testing and Performance Verification Methodologies for Biosafety Level 3 (BSL-3) and Animal Biosafety Level 3 (ABSL-3) HVAC Systems]. This standard directly outlines the specific testing and performance verification methodologies required for commissioning and the mandatory ongoing recertification of BSL-3 HVAC containment systems.

Designing for Whole-Room Decontamination and Fumigation

Achieving a Gas-Tight Envelope

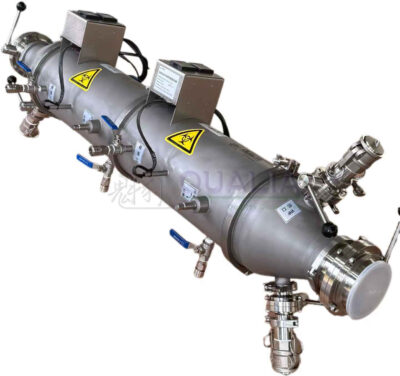

The entire laboratory envelope, including all ductwork, must be sealed to be gas-tight to permit fumigation. All penetrations for ducts, pipes, and cables require permanent seals. Surfaces must be smooth, impervious, and chemical-resistant. This design requirement directly impacts material selection, favoring specialized components like 304 stainless steel.

Material and Supply Chain Implications

These materials are part of a specialized, high-assurance supply chain. The ability to effectively fumigate is a critical benchmark during the evaluation of existing systems. Any compromise in envelope integrity represents a significant containment risk that must be remediated. This often involves invasive testing like static pressure decay tests.

Integration with HVAC Design

The HVAC system itself must support fumigation. Dampers must seal completely, and system controls must allow for a sealed, static environment during the decontamination cycle. Post-fumigation purge cycles must be carefully designed to safely evacuate the decontaminant without compromising containment.

Evaluating and Maintaining an Operational BSL-3 System

Ongoing Conformance and Condition Assessment

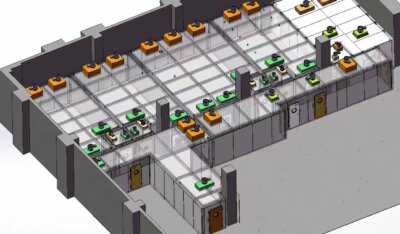

Ongoing evaluation involves verifying conformance to original specifications and assessing the physical condition of all components. Calibrating sensors annually is essential for data integrity. Maintenance personnel must fully understand system operation and failure modes. This evaluation reveals the market stratification into fixed, modular, and mobile tiers.

The Trend Toward Digital Management

For all tiers, the trend is toward integrated digital monitoring. This supports continuous evaluation and enables a shift from reactive maintenance to predictive analytics. Data from the BMS can inform filter change-outs, bearing replacements, and control system updates before failures occur. This transforms facility management into a data-driven practice.

Lifecycle Management Strategies

While fixed facilities require sustained lifecycle investment, mobile BSL-3 labs represent a different paradigm. Their challenge shifts from construction to logistics and deployment of pre-validated systems. The evaluation criteria, however, remain focused on proven containment performance and the rigor of recertification protocols.

The primary decision points center on integration, verification, and lifecycle management. Prioritize a design where primary and secondary containment are co-engineered, not separately specified. Insist on performance-verified outcomes through pre-construction CFD modeling and rigorous commissioning against relevant standards. Finally, choose a maintenance and certification strategy that treats the HVAC system as a living, critical component requiring continuous data-driven evaluation.

Need professional guidance to implement or validate a BSL-3 containment system? The engineers at QUALIA specialize in the integrated design and performance verification of high-consequence biocontainment infrastructure. Contact us to discuss your project requirements. Contact Us

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What is the minimum negative pressure differential required for a BSL-3 lab, and what is the recommended design target?

A: The minimum required differential is -12.5 Pa (-0.05″ water gauge) between the laboratory and adjacent spaces. However, expert design practice targets -25 Pa to establish a critical safety margin against pressure fluctuations and routine disturbances. This means facilities planning for high-risk work or variable internal loads should design their control systems to reliably maintain this higher benchmark for enhanced containment assurance, as outlined in foundational guidelines like the CDC/NIH BMBL.

Q: How do you integrate a hard-ducted biosafety cabinet with the room’s HVAC system without disrupting containment?

A: Successful integration requires the room’s exhaust system to be designed to accommodate the cabinet’s specific airflow, ensuring the total exhaust balance maintains the required negative pressure cascade. This complex coordination is best validated with advanced Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) modeling to simulate interactions under all operational states. For projects retrofitting cabinets into existing labs, expect significant challenges in balancing legacy ductwork with new equipment, often making it a major, complex undertaking.

Q: What are the essential components of a fail-safe design for BSL-3 HVAC redundancy?

A: A true fail-safe design extends beyond N+1 fan redundancy to include Uninterruptible Power Supplies (UPS), emergency generators, redundant sensors, and control processors with automatic failover logic. The system architecture must ensure that any single failure, like a fan loss, cannot cause a dangerous pressure reversal, often using dampers that close to maintain directional airflow. This operational principle directly equates system reliability with containment safety, so capital planning must account for these high-assurance components and their associated supply chain.

Q: Why is whole-room fumigation capability a critical design consideration for BSL-3 labs?

A: The entire laboratory envelope, including all ductwork, must be sealed gas-tight to permit effective decontamination using agents like vaporized hydrogen peroxide. This requirement dictates material selection, favoring smooth, impervious, and chemical-resistant surfaces like 304 stainless steel, and mandates permanent seals on all penetrations. If you are evaluating an existing facility for upgrade, any compromise in this envelope integrity represents a major containment risk that must be remediated before the lab can be certified for use.

Q: What is the role of the airlock in a negative pressure cascade, beyond being a sealed door?

A: The airlock functions as an actively controlled pressure transition zone, engineered to maintain the unidirectional airflow gradient during personnel entry and exit. It is a critical subsystem that preserves the integrity of the layered containment defense when the cascade is most vulnerable. This means your control system design must prioritize rapid, dynamic response to pressure disturbances caused by door operations to prevent momentary reversals that could compromise safety.

Q: How does ongoing certification impact the operational lifecycle and cost of a BSL-3 facility?

A: Mandatory annual recertification involves retesting pressure differentials, HEPA filter integrity, and all alarm responses, which requires scheduled operational downtime. This process is a non-negotiable legal and safety imperative to verify continued containment performance. Therefore, your facility’s lifecycle cost model and operational schedule must explicitly account for these recurring expenses and downtime windows to maintain regulatory compliance and insurance validity.

Q: What advantage does integrated digital monitoring provide for maintaining a BSL-3 containment system?

A: A Building Management System (BMS) that provides continuous, real-time monitoring of pressure, airflow, and filter status acts as the facility’s central nervous system. It enables predictive maintenance through trend analysis and transforms system management into a data-driven practice. For operations seeking higher reliability, this integration supports a shift from merely owning hardware to considering performance-guaranteed “containment-as-a-service” models from specialized vendors.

Related Contents:

- BSL-4 Pressure Cascades: Advanced System Design

- BSL-4 Air Handling: Critical System Requirements

- BSL-3 Lab Ventilation: Design for Optimal Safety

- BSL 2/3/4 HVAC System Design: Pressure Cascade, ACH Rates & Directional Airflow Engineering Requirements

- Air Handling in BSL-3 vs BSL-4: System Comparison

- Biosafety Cabinet Exhaust Systems Explained

- Installing Modular BSL-3 Labs: Expert Guide

- BSL-4 Lab Airflow Control: Ensuring Biosafety

- BSL-3 Air Handling: Critical Unit Requirements