Laboratory effluent decontamination is a critical containment function, yet its requirements are often misunderstood as a simple scaling of capacity. The core challenge for facility managers and biosafety officers is navigating the distinct, non-linear regulatory and engineering escalations from BSL-2 to BSL-4. Misapplying BSL-2 point-source strategies to a BSL-3 environment, or underestimating the fail-safe redundancy needed for BSL-4, creates significant compliance and safety vulnerabilities.

Attention to this issue is paramount now, as global biosecurity standards tighten and laboratory construction accelerates. Selecting and validating an Effluent Decontamination System (EDS) is not a procurement exercise but a foundational risk management decision. The system must align precisely with the biosafety level’s mandates, the specific waste stream characteristics, and an increasingly rigorous validation paradigm that borrows from pharmaceutical standards.

Core Differences Between BSL-2, BSL-3, and BSL-4 EDS Requirements

Defining the Regulatory Threshold

The BMBL establishes a clear demarcation in effluent handling philosophy. At BSL-2, the focus is on prudent practice rather than engineered containment. Liquid waste from specific processes is typically inactivated at the point of generation, often via an autoclave or chemical treatment bench-side, before disposal into the sanitary sewer where local codes permit. This approach, however, carries hidden risks. Research indicates that autoclaves can expel viable microorganisms through the chamber drain during the initial air purge cycle, a critical vulnerability that must be assessed in the facility’s risk assessment.

The Shift to Centralized Containment

BSL-3 mandates a fundamental shift to engineered, centralized decontamination. All wastewater originating from the containment zone—including sink, shower, and equipment drain effluent—must be collected and treated by a validated system before release. This includes often-overlooked streams like condensate from HEPA filter housings or air handling units. The system itself becomes a primary barrier, moving from a supportive practice to a critical piece of safety infrastructure where performance is non-negotiable.

The Absolute Containment Imperative

BSL-4 requirements represent the apex of biosafety engineering. All liquid waste must be decontaminated within the maximum containment area itself via a dedicated, fail-safe system. The concept of “system failure” is not an option; design must guarantee treatment under any foreseeable fault condition. This progression underscores that EDS evolution is not linear but exponential, moving from administrative control to redundant, safety-critical systems integrated into the facility’s core containment strategy.

| Biosafety Level | EDS Requirement | Key Operational Focus |

|---|---|---|

| BSL-2 | Point-source decontamination only | On-site autoclave/chemical treatment |

| BSL-3 | Centralized system mandatory | All lab wastewater treatment |

| BSL-4 | Fail-safe, dedicated system | Absolute containment; no failure option |

Source: Technical documentation and industry specifications.

Technical Standards by Biosafety Level: CDC/NIH BMBL Guide

BMBL as the Foundational Framework

The CDC/NIH Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories (BMBL) provides the definitive technical framework for U.S. laboratories. Its guidelines form the basis for institutional biosafety manuals and facility design standards. For effluent, the BMBL’s language is precise and escalates with risk. It permits BSL-2 facilities to drain to sanitary sewers if local codes allow, emphasizing in-lab treatment of collected waste. The explicit mandate for a centralized system begins at BSL-3.

Navigating the Method Preference

A key strategic insight from the BMBL and related guidelines is the stated preference for thermal decontamination methods. Chemical methods are permissible if validated, but this allowance creates a nuanced compliance landscape. In my experience, a chemically based EDS, while potentially compliant, often invites greater scrutiny during audits and requires a more extensive, defensible validation dossier to support the risk assessment compared to a thermal system, which aligns with the regulatory preference.

Interpreting “All Effluent”

At BSL-3 and above, the requirement to treat “all effluent” has specific interpretations. It encompasses not just intentional waste but also accidental releases, shower runoff, and condensate. This broad scope directly impacts system sizing and technology selection. Engineers must account for peak flow rates from emergency shower activation, which can be substantial, ensuring the EDS has the capacity and holding capability to manage these surge events without compromising containment.

| Biosafety Level | Effluent Handling Standard | Decontamination Method Preference |

|---|---|---|

| BSL-2 | Sanitary sewer (if allowed) | In-lab treatment of collected waste |

| BSL-3 | All containment zone effluent | Validated centralized EDS |

| BSL-4 | Sealed, heat-traced lines | Thermal preferred; chemical if validated |

Source: Technical documentation and industry specifications.

Validating EDS Efficacy: Biological Indicators and Log Reduction

The 6-Log Reduction Benchmark

Validation is the process that proves an EDS achieves a minimum 6-log10 reduction of resistant microbial spores, effectively sterilizing the effluent. This isn’t a suggestion but a mandatory performance threshold. The selection of the appropriate biological indicator (BI) is critical and method-dependent. For thermal systems, Geobacillus stearothermophilus spores are the standard, chosen for their high heat resistance. They must be placed in the treatment vessel’s coldest spot, typically determined during a temperature mapping study, to challenge the system’s weakest point.

The Pitfalls of Chemical Validation

Validating chemical EDS is inherently more complex than thermal validation. It requires demonstrating efficacy against high spore loads within a simulated organic waste matrix that mirrors the actual laboratory effluent. A common and critical mistake is using commercial spore strips in Tyvek packets. Spores can wash off these strips during the treatment cycle, making it impossible to distinguish between true inactivation and physical removal, thus invalidating the test. Facilities must adopt more rigorous methods, such as laboratory-prepared spore suspensions or encapsulated spores.

The Specificity of Agent Validation

For chemical systems using bleach, a major variable is product specificity. Validation must be conducted with the exact bleach product and concentration intended for operational use. Relying on generic sodium hypochlorite concentration specifications is inadequate, as proprietary stabilizers, pH, and age can dramatically affect sporicidal efficacy in complex waste matrices. The validation protocol must account for the product’s degradation over its shelf life within the facility’s storage conditions.

| Validation Parameter | Requirement/Standard | Key Implementation Detail |

|---|---|---|

| Log Reduction | Minimum 6-log10 reduction | Against resistant microbial spores |

| Thermal System BI | Geobacillus stearothermophilus | Placed in coldest spot |

| Chemical Validation | High spore loads in waste | Simulated organic waste matrix |

| Bleach Validation | Exact product used | Generic specs are inadequate |

Source: Technical documentation and industry specifications.

Operational Design: Thermal vs. Chemical Decontamination Systems

Batch and Continuous Thermal Systems

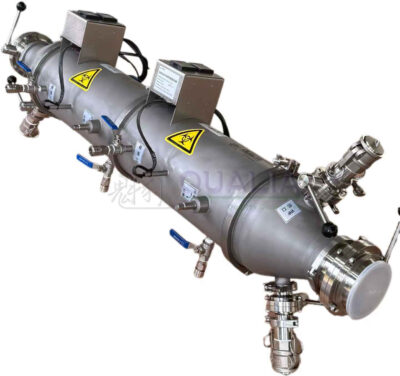

Thermal systems operate by destroying pathogens through heat. Batch systems collect effluent in a sealed “kill tank,” heat it to a set temperature (e.g., 121°C), and hold it for a validated time. Continuous flow systems pass effluent through a heat exchanger for rapid heating to a higher temperature with a shorter hold time. The choice between batch and continuous often hinges on waste stream characteristics and facility workflow. Batch systems with energy recovery can offer significantly lower operating costs over time, a factor often underestimated in initial procurement analyses.

The Operational Burden of Chemical Systems

Chemical decontamination systems use a controlled contact tank where a high concentration of a sporicidal agent like bleach is mixed with effluent. While sometimes lower in initial capital cost, this technology imposes substantial long-term operational burdens. It requires complex neutralization of the effluent before sewer discharge to meet local pH standards, creates hazardous chemical byproducts, and demands a massive, ongoing logistical chain for the supply, storage, and handling of bulk bleach. The total lifecycle cost analysis frequently reveals chemical systems to be more expensive and labor-intensive.

Making the Technology Decision

The technology selection is not merely a capital purchase decision but a commitment to a specific operational model for the facility’s lifespan. It balances regulatory preference, waste stream compatibility (e.g., high salt or organic content can interfere with chemical efficacy), safety of chemical handling, and total cost of ownership. The trend in modern high-containment labs favors thermal systems, particularly those with advanced energy recovery, for their operational simplicity, predictable performance, and alignment with regulatory expectations for preferred methods.

| System Type | Primary Mechanism | Key Long-Term Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Batch Thermal | “Kill tank” heat & hold | Lower operating costs possible |

| Continuous Flow Thermal | Heat exchanger | Rapid heating of effluent |

| Chemical | Controlled contact tank | Complex neutralization required |

Note: Chemical systems require massive logistical support for bleach supply and create hazardous byproducts.

Source: Technical documentation and industry specifications.

Key Considerations for BSL-3 and BSL-4 EDS Redundancy & Safety

Engineering Redundancy Standards

Redundancy is the engineered response to the imperative of continuous containment. For BSL-3, an N+1 configuration—having a fully functional backup treatment tank—is a critical design consideration. This allows one tank to be serviced or repaired while the other remains operational, preventing the facility from having to shut down. At BSL-4, this escalates to fully redundant systems, often with Safety Integrity Level (SIL)-rated controls, designed to guarantee treatment even in the event of a primary system component failure.

Maintaining Secondary Containment

The EDS itself must maintain the containment boundary. Feed lines from the lab should incorporate air breaks or other backflow prevention devices to protect the lab environment. Tank vents may require HEPA filtration to prevent the release of aerosols during filling or heating cycles, especially if there is a risk of foaming or boiling. These features ensure the EDS acts as a true extension of the lab’s containment envelope, a principle reinforced by standards like BS EN 1717:2000 for protecting potable water from backflow contamination.

The Data-Driven EDS

Modern EDS have evolved into critical data nodes within the biosafety infrastructure. Systems with full automation, PLC controls, and data logging provide traceability for every decontamination cycle, recording time, temperature, pressure, and cycle status. This transforms the EDS from a simple utility into a source of validated compliance data, supporting not only regulatory audits but also proactive facility risk management and trend analysis.

| Biosafety Level | Redundancy Standard | System Evolution |

|---|---|---|

| BSL-3 | N+1 configuration (backup tank) | Ensures continuous operation |

| BSL-4 | Redundant tanks & controls (SIL-rated) | Guarantees treatment; no failure |

| All High-Containment | HEPA-filtered tank vents | Maintains containment integrity |

Source: ANSI/ASSE Z9.14-2021 Testing and Performance Verification Methodologies for Biosafety Level 3 (BSL-3) and Animal Biosafety Level 3 (ABSL-3) HVAC Systems. This standard’s rigorous performance verification philosophy for critical containment systems directly parallels the need for fail-safe design and validated redundancy in high-containment EDS, ensuring overall biosafety integrity.

Integrating EDS with Laboratory Waste Streams and Containment

Conducting a Waste Stream Audit

Effective EDS design is impossible without a detailed audit of the actual waste stream. This non-negotiable prerequisite analyzes flow rate, peak and average daily volume, solids content, viscosity, pH, and chemical composition. High solids or fibrous material may necessitate pre-maceration equipment. Corrosive streams dictate specific materials of construction, such as 316L stainless steel or more exotic alloys. This analysis directly determines technology suitability; for example, batch systems are often better suited for variable or high-solids effluents than continuous flow designs.

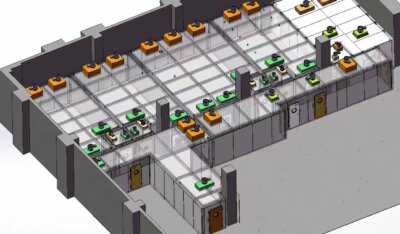

The Rise of Integrated Waste Treatment

An emerging trend is the move toward integrated waste treatment ecosystems. Advanced systems are now designed to handle both solid infectious waste (in a pass-through autoclave) and liquid effluent. All resultant condensate and rinse water from the solid waste treatment is discharged directly to the integrated liquid EDS. This creates a closed-loop process entirely within the containment barrier, eliminating the manual handling and transfer risks associated with separate systems and simplifying the overall waste management protocol.

Sizing for Real-World Conditions

Sizing an EDS requires planning for both routine operations and contingency events. The system must handle the baseline daily effluent volume but also be sized to accommodate large, intermittent flows from equipment dump cycles or the mandatory 15-minute emergency shower flow. Under-sizing leads to operational bottlenecks and potential containment breaches; over-sizing increases capital and energy costs unnecessarily. The audit must capture these peak demand scenarios to inform correct capacity planning for liquid effluent decontamination systems.

| Design Factor | Prerequisite Analysis | Technology Suitability |

|---|---|---|

| Solids Content | Pre-maceration may be required | Batch systems often better |

| Stream Corrosivity | Materials selection (e.g., 316L SS) | Dictates vessel construction |

| Flow Rate & Volume | Daily volume audit | Determines system capacity |

| Integrated Treatment | Handles solid & liquid waste | Closed-loop process within containment |

Source: Technical documentation and industry specifications.

Compliance, Recordkeeping, and Navigating Local Discharge Codes

The Layered Regulatory Landscape

Compliance requires navigating a layered regulatory environment. Federal guidelines like the BMBL set the minimum biosafety standard, but local publicly owned treatment works (POTW) discharge codes are often more stringent. These local codes govern pH, temperature, chemical oxygen demand (COD), and residual disinfectant levels. A system compliant with BMBL may violate local codes if, for example, chemically treated effluent is not properly neutralized before discharge. Early engagement with local authorities is essential.

Meticulous Lifecycle Documentation

Recordkeeping is the evidence of compliance. Detailed logs must be maintained for every EDS cycle, including date/time, cycle parameters, operator, and any deviations. Maintenance records, calibration certificates for sensors, and, most importantly, the complete validation package (IQ/OQ/PQ) are essential for audits. The validation approach itself is converging on pharmaceutical-grade lifecycle standards, moving beyond simple parameter checks to a holistic proof of consistent, validated performance over the system’s operational life.

Validation as a Continuous Process

Routine re-validation and periodic challenge testing are required to ensure ongoing efficacy. This includes annual re-qualification with biological indicators and any re-validation following significant changes to the waste stream, maintenance on critical components, or relocation of the system. This continuous verification mindset ensures the EDS remains a reliable component of the containment strategy, adapting to the evolving operational profile of the laboratory.

| Compliance Area | Core Requirement | Operational Complexity |

|---|---|---|

| Recordkeeping | Detailed cycle parameter logs | Essential for audits |

| Discharge Codes | Meet local sewer standards | Often more stringent than BMBL |

| Chemical Effluent | Neutralization & pH adjustment | Adds processing steps |

| Validation Methodology | IQ/OQ/PQ lifecycle standards | Pharmaceutical-grade benchmark |

Source: BS EN 1717:2000 Protection against pollution of potable water in water installations and general requirements of devices to prevent pollution by backflow. This standard underpins the critical need to prevent backflow contamination from laboratory effluent systems into potable water supplies, a fundamental safety principle that informs local discharge codes and overall EDS integration design.

Implementing a risk-based EDS framework begins with an agent-specific hazard assessment, directly informing the required log reduction and performance specification. Technology selection must then balance regulatory preference, waste stream reality, and a rigorous total lifecycle cost analysis, where energy recovery and sustainability are now key drivers. Finally, a scientifically sound validation protocol must prove lethality in the real-world waste matrix, employing challenge methods that eliminate ambiguity.

This structured approach ensures the EDS is not merely a compliant purchase but a strategically optimized, safety-assured component of your containment architecture. It transforms a complex regulatory requirement into a managed, validated engineering control.

Need professional guidance on specifying and validating an EDS for your containment facility? The experts at QUALIA can help you navigate the technical standards, waste stream analysis, and validation protocols to implement a system that meets both safety and compliance imperatives.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: When is a centralized Effluent Decontamination System mandatory for a laboratory?

A: A centralized EDS treating all laboratory wastewater is required for BSL-3 and BSL-4 facilities. BSL-2 standards typically allow point-source decontamination, but centralized treatment becomes a critical engineered safety system at higher containment levels. This means your project’s biosafety level designation is the primary driver for this major capital infrastructure decision, moving from operational best practice to a non-negotiable containment requirement.

Q: How do you properly validate a 6-log reduction for a chemical EDS using bleach?

A: Validation requires proving efficacy against high spore loads in simulated organic waste, not just checking concentration. You must use the exact commercial bleach product planned for operations, as generic specifications are unreliable, and avoid commercial spore strips where spores can wash off. This means your validation protocol must be matrix-specific and scientifically rigorous to withstand regulatory scrutiny, which is often more intense for chemical systems than for thermal ones.

Q: What are the key operational trade-offs between thermal batch and chemical EDS technologies?

A: Thermal batch systems with energy recovery typically offer simpler effluent handling and lower long-term operating costs, while chemical systems introduce complexity through required neutralization, hazardous byproduct management, and significant logistical support for chemical supply. This means the initial purchase price is secondary; a total lifecycle analysis of chemical handling, waste disposal, and energy use should drive your technology selection.

Q: What does redundancy look like for an EDS in a BSL-3 or BSL-4 facility?

A: For BSL-3, an N+1 configuration with a backup treatment tank is a key design consideration for maintenance continuity. BSL-4 requires fully redundant treatment tanks and controls, often with Safety Integrity Level (SIL) ratings, to guarantee decontamination under any failure scenario. This means your containment level dictates the investment in parallel, fail-safe infrastructure, transforming the EDS from a utility into a safety-critical data node with full automation and traceability.

Q: How should laboratory waste stream characteristics influence EDS design?

A: A detailed audit of flow rate, daily volume, solids content, viscosity, and pH is a non-negotiable prerequisite. High solids may require pre-maceration, and corrosive streams demand specific materials like 316L stainless steel, making batch systems better for variable or high-solids effluents. This means your system specification must be data-driven from the start, as waste characteristics directly determine technology suitability and long-term reliability.

Q: What standards ensure potable water safety when integrating an EDS with lab plumbing?

A: Protection against backflow contamination is governed by standards like BS EN 1717:2000, which sets requirements for devices to prevent pollution of potable water installations. This standard is critical for ensuring contaminated laboratory effluent cannot back-siphon into the clean water supply. This means your plumbing integration design must include verified backflow prevention devices that comply with such codes to address a fundamental cross-connection risk.

Q: What framework should we use to select and validate an EDS for a new high-containment lab?

A: Implement a risk-based framework starting with an agent-specific hazard assessment to define the required log reduction. Technology selection must then balance regulatory preference, waste stream characteristics, and total lifecycle costs, with energy recovery becoming a key driver. This means your process should ensure the EDS is a strategically optimized, safety-assured component, not just a compliant purchase, with a validation protocol that accounts for real-world waste matrix effects.

Related Contents:

- BioSafe EDS: Thermal Systems for Effluent Treatment

- BioSafe EDS: Batch-Continuous Treatment Systems

- Waste Effluent Stream Management: BioSafe EDS

- Sterile Effluent Cooling: BioSafe’s EDS Technology

- Safeguarding Health: Advanced Effluent Decontamination Systems

- BSL-4 Effluent Treatment: BioSafe’s Ultimate EDS

- Effluent Decontamination Systems: Safeguarding Biosafety Across Levels

- Effluent Decontamination System | What Is EDS Technology | Basics Guide

- BioSafe EDS for BSL-3: Advanced Containment Solutions