Dobór bioreaktorów do produkcji szczepionek mRNA to kalkulacja o wysokiej stawce, która bezpośrednio determinuje nakłady kapitałowe, wykonalność operacyjną i odporność łańcucha dostaw. Powszechnie panuje błędne przekonanie, że dobór wielkości bioreaktora jest prostym ćwiczeniem wolumetrycznym. W rzeczywistości jest to złożony problem optymalizacyjny równoważący dawkę, wydajność procesu i ograniczenia obiektu. Błąd w początkowym modelu wymiarowania może zablokować program w nieefektywnym, kosztownym paradygmacie produkcji.

Pilna potrzeba precyzyjnego określania wielkości nasiliła się wraz z pojawieniem się platform RNA nowej generacji, takich jak samoamplifikujące się RNA (saRNA). Platformy te obiecują radykalnie niższe dawki, co zasadniczo zmienia równanie skali. Wybór niewłaściwej skali lub strategii może teraz spowodować utratę korzyści ekonomicznych i logistycznych, jakie oferują te nowe technologie. Decyzja ta dyktuje nie tylko koszty sprzętu, ale także całą architekturę sieci produkcyjnej.

Kluczowe dane wejściowe do określania wielkości: Dawka, miano i wydajność

Podstawowe równanie

Podstawowe obliczenia dotyczące objętości roboczej bioreaktora są zwodniczo proste: Objętość robocza bioreaktora (L) = [liczba dawek × RNA na dawkę (g)] / [miano (g/L) × wydajność (%)].. Wzór ten ujawnia trzy współzależne dźwignie. Ilość RNA na dawkę jest najpotężniejszym czynnikiem skalującym, różniącym się o rzędy wielkości między platformami. Miano IVT, zazwyczaj 2-7 g/L, odzwierciedla wydajność syntezy określonego konstruktu i mieszanki enzymów. Wydajność końcowa, często 50-80%, jest złożeniem strat oczyszczania i formulacji, które muszą zostać zweryfikowane empirycznie.

Dawka jako główny czynnik napędzający

Sam parametr dawki może na nowo zdefiniować strategię produkcji. Konwencjonalna szczepionka mRNA w dawce 100 µg na dawkę wymaga skali produkcji tysiące razy większej niż szczepionka saRNA w dawce 0,1 µg dla tej samej liczby dawek. Nie jest to redukcja liniowa, ale transformacyjna. Wgląd 1 podkreśla, że 1000-krotne zmniejszenie dawki może zmniejszyć wymaganą objętość bioreaktora z tysięcy litrów do mniej niż jednego litra dla globalnych dostaw. Ta zmiana sprawia, że optymalizacja dawki staje się głównym czynnikiem wpływającym na efektywność kapitałową, umożliwiając całkowicie nowe, rozproszone modele produkcji, wcześniej uważane za niepraktyczne dla globalnych dostaw szczepionek.

Kwantyfikacja zakresów wejściowych

Aby zastosować równanie, potrzebne są zatwierdzone zakresy dla każdego parametru. Branżowe wzorce stanowią punkt wyjścia, ale dane specyficzne dla procesu nie podlegają negocjacjom. Miano może się znacznie różnić w zależności od mieszanki nukleotydów i jakości plazmidowego DNA. Wydajność jest w dużym stopniu zależna od wybranej chromatografii i metod filtracji z przepływem stycznym (TFF). Z mojego doświadczenia wynika, że zespoły, które przyjmują założenie dotyczące miana przed optymalizacją procesu, często stają w obliczu kosztownych przeróbek związanych ze zwiększaniem skali.

Kluczowe dane wejściowe do określania wielkości: Dawka, miano i wydajność

| Parametr | Typowy zakres | Wpływ na wolumen |

|---|---|---|

| RNA na dawkę | 0,1 µg - 100 µg | Główny czynnik wpływający na skalowanie |

| Tytuł IVT | 2 - 7 g/L | Wydajność syntezy |

| Zysk na rynku niższego szczebla | 50% - 80% | Rozliczenie strat |

| Dawka saRNA | ~0,1 µg | Umożliwia korzystanie z bioreaktorów <10 l |

| Konwencjonalna dawka mRNA | 30 - 100 µg | Wymaga 1000x większej skali |

Źródło: ASTM E2500-20 Standardowy przewodnik dotyczący specyfikacji, projektowania i weryfikacji systemów i urządzeń do produkcji farmaceutycznej i biofarmaceutycznej. Niniejszy przewodnik zapewnia ramy do określania i weryfikacji systemów produkcyjnych w oparciu o krytyczne parametry procesu, takie jak miano i wydajność, zapewniając, że system bioreaktora jest odpowiedni do zamierzonego celu produkcyjnego.

Czynniki wpływające na koszty: Od inwestycji kapitałowych do całkowitego kosztu posiadania

Faza wydatków kapitałowych

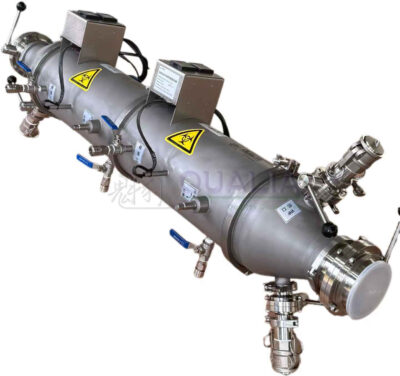

W przypadku produkcji dużych dawek mRNA, koszt kapitałowy wielkoskalowych zestawów bioreaktorów, mediów pomocniczych i samego obiektu dominuje w modelu finansowym. Obejmuje to koszt bioreaktorów ze stali nierdzewnej, systemów czyszczenia w obiegu zamkniętym (CIP) oraz wymaganego rozbudowanego orurowania i oprzyrządowania. Zgodność z normami takimi jak ASME BPE-2022 przy projektowaniu urządzeń do bioprzetwarzania zwiększa nakłady kapitałowe, ale ma zasadnicze znaczenie dla zapewnienia integralności systemu i zatwierdzenia przez organy regulacyjne.

Przesunięcie kosztów operacyjnych

Model ekonomiczny odwraca się w przypadku platform RNA o niskiej dawce. Insight 3 podkreśla, że w przypadku produkcji saRNA koszty materiałów eksploatacyjnych do sprzętu jednorazowego użytku stają się głównym wydatkiem operacyjnym, przewyższając nawet surowce. Obejmuje to jednorazowe worki do bioreaktorów, filtry i zespoły łączące. Ta zmiana sprawia, że bezpieczeństwo łańcucha dostaw i negocjowanie kosztów materiałów eksploatacyjnych stają się najważniejszymi działaniami strategicznymi, a nie kwestiami drugorzędnymi.

Podatność na surowce

Poza sprzętem, stałym zagrożeniem jest zmienność kosztów surowców. Insight 6 identyfikuje enzymy i zmodyfikowane nukleotydy jako kluczowe czynniki kosztotwórcze podlegające wahaniom rynkowym. Ryzyko to wymaga strategii zaopatrzenia, która może obejmować integrację pionową, długoterminowe umowy na dostawy lub podwójne zaopatrzenie. Niepowodzenie w zmniejszeniu ryzyka dostaw surowców może zniwelować teoretyczne korzyści kosztowe wynikające z bardziej wydajnej platformy.

Scale-Up vs. Scale-Out: Która strategia jest dla Ciebie odpowiednia?

Techniczne ograniczenia skalowania

Prawdziwe zwiększenie skali reakcji IVT jest fizycznie ograniczone. Praktyczne limity pojedynczej partii są bliskie 30 l ze względu na wyzwania związane z przenoszeniem ciepła i osiągnięciem jednorodnego mieszania w większych objętościach. Tworzy to twardy pułap dla zwiększania wielkości partii. W przypadku programów ukierunkowanych na wysokie roczne dawki, ograniczenie to natychmiast wymusza strategię skalowania - dodawanie wielu identycznych linii produkcyjnych do pracy równoległej - zamiast skalowania pojedynczej linii.

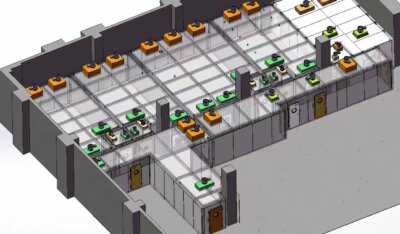

Imperatyw skalowania dla dużych wolumenów

Skalowanie obejmuje powielanie sprawdzonych procesów. Strategia ta zapewnia redundancję i upraszcza transfer technologii, ale zwiększa powierzchnię zakładu i złożoność operacyjną. Wymaga skrupulatnego planowania przepływu materiałów, personelu i kontroli jakości na równoległych liniach. Przy projektowaniu takich obiektów można skorzystać z ram opisanych w dokumencie ISPE Baseline Guide Volume 6, który dotyczy integracji wielu zestawów do bioprzetwarzania.

Możliwości produkcji rozproszonej

Insight 7 wskazuje na krytyczną możliwość: minimalne ilości wymagane dla niskich dawek saRNA (np. <10 l dla miliardów dawek) sprawiają, że rozproszona produkcja jest technologicznie wykonalna. Model ten zmniejsza zależność od ogromnych scentralizowanych zakładów, umożliwiając tworzenie suwerennych, rozproszonych geograficznie sieci produkcyjnych. Sieci te ograniczają ryzyko logistyczne i polityczne, umożliwiając szybszą reakcję regionalną. Wybór między pojedynczym dużym zakładem a siecią mniejszych jest teraz decyzją strategiczną, a nie tylko techniczną.

Jak obliczyć wymaganą objętość roboczą bioreaktora?

Wykonywanie obliczeń podstawowych

Podejście krok po kroku eliminuje niejednoznaczność. Najpierw należy zdefiniować wymaganą całkowitą masę mRNA: Dawki docelowe × RNA na dawkę. Na przykład 1 miliard dawek szczepionki 100 µg wymaga 100 000 g mRNA. Następnie należy określić wydajność procesu: pomnożyć oczekiwane miano przez wydajność. Miano 5 g/L i wydajność 60% daje 3 g końcowej substancji leczniczej na litr reakcji IVT. Wymagana objętość robocza wynosi zatem 100 000 g / 3 g/L ≈ 33 333 L.

Zastosowanie analizy wrażliwości

Model nie jest jednakowo wrażliwy na wszystkie dane wejściowe. Dawka RNA ma wpływ wykładniczy, następnie miano, a potem wydajność. Należy uruchomić scenariusze z górną i dolną granicą każdego parametru. Miano, które spada z 5 g/L do 4 g/L zwiększa wymaganą objętość o 25%. Zawsze należy uwzględnić margines - zazwyczaj ±20% - aby uwzględnić zmienność miana podczas opracowywania procesu i zwiększania skali. Bufor ten zapobiega niedoborom wydajności.

Od wolumenu do strategii

Liczba wyjściowa dyktuje kolejne decyzje. Wynik liczony w dziesiątkach tysięcy litrów potwierdza, że mamy do czynienia z wielkoskalową, wieloliniową instalacją. Wynik poniżej 50 litrów otwiera drzwi do systemów jednorazowego użytku i elastycznych instalacji. Obliczenia te stanowią niezbywalny punkt wyjścia dla wszystkich dalszych prac projektowych.

Jak obliczyć wymaganą objętość roboczą bioreaktora?

| Krok obliczeniowy | Przykładowa wartość | Wynik / Uwaga |

|---|---|---|

| Dawki docelowe | 1 miliard dawek | Określa cel produkcyjny |

| RNA na dawkę | 100 µg | = 100 000 g całkowitego mRNA |

| Wydajność procesu (miano x wydajność) | 5 g/L x 60% = 3 g/L | Końcowa substancja lecznicza na litr |

| Wymagana objętość robocza | 100 000 g / 3 g/L | ≈ 33 333 litry |

| Zalecany margines | ±20% | Dla zmienności miana |

Źródło: Dokumentacja techniczna i specyfikacje branżowe.

Wąskie gardła procesu: IVT, oczyszczanie i formułowanie LNP

Przeoczone ograniczenie LNP

Podczas gdy synteza IVT często cieszy się największym zainteresowaniem, Insight 2 zapewnia krytyczną korektę: Enkapsulacja LNP poprzez mieszanie mikroprzepływowe jest często etapem ograniczającym szybkość produkcji substancji leczniczych. Jego przepustowość (litry na godzinę) może być niższa niż objętość wyjściowa etapu IVT. To niedopasowanie może prowadzić do bezczynności kosztownych bioreaktorów lub wymagać inwestycji w wiele równoległych urządzeń mieszających, które muszą być dobrane pod względem wielkości i zakwalifikowane zgodnie ze skalą IVT.

Strata wydajności w procesie oczyszczania

Oczyszczanie poprzez chromatografię i TFF nie jest transferem 1:1. Zazwyczaj wprowadza utratę 20-30% masy mRNA. Ta wydajność musi być uwzględniona we wstępnych obliczeniach wielkości. Co więcej, etapy te mają swoje własne czasy cyklu i limity wydajności przygotowania buforu i postępowania z odpadami, co może ograniczać planowanie partii.

Krytyczna zależność od wyższego szczebla

Insight 5 podkreśla słabość przed bioreaktorem: wszystkie platformy mRNA zależą od skalowalnego, wysokiej jakości szablonu plazmidowego DNA (pDNA). produkcja pDNA, zwykle w E. coli Fermentacja jest oddzielnym procesem z własnymi wyzwaniami skalowania i długim czasem realizacji. Wąskie gardło w produkcji pDNA może zatrzymać całą linię produkcyjną mRNA, co sprawia, że jest to krytyczny element ścieżki, często niedoceniany w początkowych obliczeniach wielkości bioreaktora.

Wąskie gardła procesu: IVT, oczyszczanie i formułowanie LNP

| Działanie urządzenia | Wspólne ograniczenie | Wpływ na przepustowość |

|---|---|---|

| Synteza IVT | Limit wsadu ~30 l | Ogranicza rzeczywiste zwiększenie skali |

| Enkapsulacja LNP | Szybkość mieszania mikroprzepływowego | Często główne wąskie gardło |

| Oczyszczanie (TFF/chromatografia) | 20-30% utrata wydajności | Znacząca redukcja masy |

| Dostawa plazmidowego DNA | Skalowalność i jakość | Krytyczna zależność upstream |

| Wypełnienie-wykończenie | Prędkość fiolkowania | Może stanowić wąskie gardło dla wysokowydajnych DS |

Źródło: ISPE Baseline Guide Volume 6: Zakłady produkcji biofarmaceutycznej (wydanie drugie). Niniejszy przewodnik dotyczy projektowania instalacji dla zintegrowanych bioprocesów, podkreślając potrzebę zrównoważenia przepustowości w połączonych operacjach jednostkowych, takich jak oczyszczanie i formulacja, aby uniknąć wąskich gardeł.

Rozważania operacyjne: Harmonogram wsadowy i dopasowanie obiektu

Obliczanie rocznej wydajności

Roczna zdolność produkcyjna to nie tylko ilość partii; to ilość pomnożona przez częstotliwość kampanii. Czas cyklu serii - obejmujący IVT, oczyszczanie, formułowanie, czyszczenie/zmianę i zwolnienie QC - określa, ile serii może uruchomić pojedyncza linia w ciągu roku. Testowanie QC, zwłaszcza testowanie sterylności, może być ukrytym wąskim gardłem w scenariuszach szybkiego reagowania, dodając tygodnie do osi czasu zwolnienia.

Zator w wypełnianiu i wykańczaniu

Insight 4 ujawnia kolejne ograniczenie, które pojawia się wraz z wydajnymi procesami: wysokowydajna produkcja mRNA na małą skalę może generować substancję leczniczą dla miliardów dawek szybciej niż konwencjonalne linie do napełniania i wykańczania mogą je fiolkować. To niedopasowanie może stworzyć zapasy substancji leczniczej luzem, wymagając kosztownego przechowywania w chłodni i komplikując logistykę. Planowanie musi albo integrować szybkie, zaawansowane technologie napełniania i wykańczania, albo uwzględniać gromadzenie zapasów w modelu łańcucha dostaw.

Integracja mediów i obiektów

Bioreaktor nie działa w izolacji. Wymaga wody o wysokiej czystości, czystej pary i gazów. Systemy do generowania Woda do wstrzykiwań (WFI), regulowane przez standardy takie jak ISO 22519:2020, muszą być dostosowane do harmonogramu wsadów i potrzeb w zakresie czyszczenia. Fizyczna powierzchnia bioreaktorów, zbiorników zbiorczych i urządzeń końcowych musi mieścić się w sklasyfikowanej przestrzeni pomieszczenia czystego, z odpowiednim miejscem na konserwację i dostęp operatora. Bioreaktor, który ma idealne wymiary na papierze, może być niemożliwy do zainstalowania lub obsługi w istniejącym układzie obiektu.

Porównanie bioreaktorów jednorazowych z bioreaktorami ze stali nierdzewnej

Argumenty przemawiające za systemami jednorazowego użytku

W przypadku objętości roboczych poniżej 50 l - co obejmuje większość platform RNA nowej generacji - bioreaktory jednorazowego użytku oferują decydujące korzyści. Eliminują konieczność walidacji czyszczenia, drastycznie zmniejszają ryzyko zanieczyszczenia krzyżowego i umożliwiają szybką zmianę produktów. Ta elastyczność jest niezbędna dla CDMO lub firm prowadzących kampanie obejmujące wiele produktów. Ich niższe nakłady kapitałowe obniżają również barierę wejścia dla nowych zakładów produkcyjnych.

Ekonomia stali nierdzewnej

Bioreaktory ze stali nierdzewnej stają się bardziej ekonomiczne w przypadku bardzo dużych, dedykowanych, ciągłych serii produkcyjnych. Oferują one niższy koszt w przeliczeniu na litr przy ogromnej skali i pozwalają uniknąć powtarzających się wydatków na materiały eksploatacyjne. Wymagają one jednak wyższych początkowych nakładów kapitałowych, rozbudowanych systemów CIP i dłuższych czasów przezbrajania w celu czyszczenia i walidacji. Stanowią one zobowiązanie do produkcji jednego produktu w jednym miejscu.

Porównanie całkowitego kosztu posiadania

Decyzja nie może opierać się wyłącznie na kosztach kapitałowych. Niezbędna jest analiza całkowitego kosztu posiadania (TCO) w całym cyklu życia projektu. W przypadku urządzeń jednorazowego użytku, model jest zdominowany przez koszty materiałów eksploatacyjnych (Insight 3). W przypadku stali nierdzewnej jest on zdominowany przez amortyzację kapitału, konserwację i walidację czyszczenia. Punkt rentowności zależy od skali, częstotliwości partii i kosztu kapitału.

Porównanie bioreaktorów jednorazowych z bioreaktorami ze stali nierdzewnej

| Czynnik decyzyjny | Bioreaktory jednorazowego użytku | Bioreaktory ze stali nierdzewnej |

|---|---|---|

| Optymalna skala | < 50 litrów | Bardzo duże, dedykowane biegi |

| Inwestycje kapitałowe | Niższy | Wyższy |

| Dominujący czynnik kosztotwórczy | Materiały eksploatacyjne (OpEx) | Amortyzacja kapitału (CapEx) |

| Czas przełączenia | Krótszy, bardziej elastyczny | Dłuższy, mniej elastyczny |

| Kluczowa zaleta | Brak walidacji czyszczenia | Korzyści skali |

Źródło: Sprzęt do przetwarzania biologicznego ASME BPE-2022. Norma ta określa wymagania projektowe i produkcyjne zarówno dla jednorazowego, jak i stałego sprzętu do bioprzetwarzania, zapewniając integralność systemu i zgodność z normami higienicznymi krytycznymi dla produkcji mRNA.

Ramy decyzyjne dla doboru wielkości i wyboru bioreaktora

Rozpocznij od ostatecznych obliczeń przy użyciu dawki docelowej, zatwierdzonego miana i oczekiwanej wydajności. Liczba ta dyktuje uniwersum możliwych urządzeń. Następnie należy ocenić, czy ta objętość wymaga strategii skalowania, czy też umożliwia zastosowanie podejścia rozproszonego z jednym pociągiem, zgodnie z sugestią Insight 7. Niezwłocznie przeprowadź analizę wąskich gardeł, aby upewnić się, że formulacja LNP i zdolności napełniania i wykańczania są dopasowane do wydajności IVT.

Następnie należy ocenić typ sprzętu przez pryzmat TCO, który nadaje priorytet dominującym czynnikom kosztowym: materiałom eksploatacyjnym w przypadku jednorazowego użytku lub kapitałowi w przypadku stali nierdzewnej. Insight 10 Sugeruje wykorzystanie symulacji cyfrowych bliźniaków do modelowania tych interakcji i optymalizacji projektu obiektu przed rozpoczęciem budowy. Na koniec należy nałożyć czynniki strategiczne: bezpieczeństwo łańcucha dostaw surowców (Insight 6), pożądaną odporność sieci i strategię regulacyjną. To systematyczne, zintegrowane podejście wykracza poza prostą matematykę w kierunku holistycznej strategii produkcji.

Precyzyjny dobór wielkości bioreaktora jest kamieniem węgielnym opłacalnego programu produkcji mRNA. Decyzja zależy od dawki platformy, jasnego spojrzenia na wąskie gardła procesu i wyboru sprzętu w oparciu o TCO. Błędy w tym zakresie przekładają się kaskadowo na zawyżone koszty i ograniczoną podaż. Potrzebujesz profesjonalnego doradztwa w zakresie modelowania konkretnej skali produkcji mRNA i zaprojektowania zoptymalizowanej strategii bioprocesowej? Zespół w QUALIA specjalizuje się w integracji operacji jednostkowych wyższego i niższego szczebla dla zaawansowanych środków terapeutycznych. Aby uzyskać szczegółowe konsultacje dotyczące projektu, możesz również Kontakt.

Często zadawane pytania

P: Jak obliczyć objętość roboczą bioreaktora potrzebną do naszej kampanii szczepionek mRNA?

O: Wymaganą objętość określa się dzieląc całkowitą masę mRNA (dawki docelowe pomnożone przez ilość RNA na dawkę) przez wydajność procesu (miano IVT pomnożone przez wydajność). Na przykład, 1 miliard dawek po 100 µg każda z mianem 5 g/L i wydajnością 60% wymaga około 33 333 litrów. Obliczenia te oznaczają, że należy wcześnie przeprowadzić analizę wrażliwości dawki, miana i wydajności, ponieważ 1000-krotne zmniejszenie dawki może zmniejszyć zapotrzebowanie bioreaktora z tysięcy litrów do mniej niż jednego.

P: Jakie są główne czynniki kosztotwórcze dla zakładu produkcji mRNA i jak zmieniają się one wraz z technologią platformy?

O: Inwestycje kapitałowe w wielkoskalowe zestawy bioreaktorów dominują w przypadku konwencjonalnego, wysokodawkowego mRNA. W przypadku platform saRNA nowej generacji o niskich dawkach, całkowity koszt posiadania ulega odwróceniu, a koszty materiałów eksploatacyjnych jednorazowego użytku stają się dominującym wydatkiem operacyjnym, przewyższającym koszty surowców. Ta zmiana sprawia, że bezpieczeństwo łańcucha dostaw materiałów jednorazowego użytku i zarządzanie zmiennością kosztów surowców dla enzymów i nukleotydów ma kluczowe znaczenie. Jeśli oceniasz platformę niskodawkową, zaplanuj negocjowanie umów na materiały eksploatacyjne i zbadaj strategie integracji pionowej, aby zmniejszyć ryzyko długoterminowej ekonomiki produkcji.

P: Kiedy powinniśmy wybrać strategię scale-out zamiast skalowania pojedynczej partii bioreaktora?

O: Wybierz skalowanie przy użyciu wielu równoległych linii, gdy wymagana objętość robocza przekracza praktyczne limity syntezy IVT dla pojedynczej partii, które są ograniczone do około 30 litrów z powodu mieszania i wymiany ciepła. Jest to typowe dla dużych dawek i dużych objętości. Z drugiej strony, minimalne objętości potrzebne dla niskich dawek saRNA (np. poniżej 10 litrów dla miliardów dawek) umożliwiają rozproszony model produkcji. W przypadku projektów mających na celu suwerenne lub szybkie reagowanie na dostawy, ta wykonalność dla geograficznie rozproszonych sieci zmniejsza ryzyko logistyczne i polityczne w porównaniu z pojedynczym masywnym zakładem.

P: Która operacja jednostkowa najprawdopodobniej stanie się wąskim gardłem w produkcji substancji leczniczej mRNA?

O: Podczas gdy synteza IVT jest często w centrum uwagi, enkapsulacja nanocząstek lipidowych (LNP) poprzez mieszanie mikroprzepływowe często staje się głównym ograniczeniem przepustowości, a jej wydajność jest potencjalnie niższa niż wydajność IVT. Oczyszczanie również wprowadza znaczne straty wydajności. Co więcej, skalowalne zaopatrzenie w wysokiej jakości matrycę plazmidowego DNA jest krytycznym, często pomijanym czynnikiem. Oznacza to, że projekt zakładu musi zrównoważyć wydajność formulacji LNP z wydajnością IVT i zabezpieczyć łańcuch dostaw pDNA, aby uniknąć zablokowania ścieżki krytycznej w harmonogramie produkcji.

P: Jak wypadają bioreaktory jednorazowego użytku w porównaniu z bioreaktorami ze stali nierdzewnej do produkcji mRNA i jakie są kluczowe kryteria wyboru?

O: Systemy jednorazowego użytku oferują znaczne korzyści w przypadku małych objętości (<50 l), powszechnych w produkcji małych dawek RNA: eliminują walidację czyszczenia, zmniejszają ryzyko zanieczyszczenia i zwiększają elastyczność wielu produktów. Jednak koszty materiałów eksploatacyjnych dominują nad kosztami operacyjnymi. Stal nierdzewna staje się bardziej ekonomiczna w przypadku bardzo dużych, dedykowanych, ciągłych kampanii, ale wymaga wyższego kapitału i dłuższych czasów wymiany. Wybór musi opierać się na całkowitym koszcie posiadania, a w przypadku elastycznych, rozproszonych modeli produkcyjnych, jednorazowe użycie często najlepiej pasuje do potrzebnej elastyczności, jak zauważono w przewodnikach projektowania obiektów, takich jak ISPE Baseline Guide Volume 6.

P: Jakie względy operacyjne poza wielkością partii wpływają na roczną wydajność produkcyjną?

O: Roczna produkcja zależy od czasu cyklu wsadowego - obejmującego IVT, oczyszczanie, formułowanie, czyszczenie i QC - który dyktuje, ile wsadów może uruchomić linia. Testowanie QC może być ukrytym wąskim gardłem w scenariuszach szybkiego reagowania. Kolejnym ograniczeniem jest to, że wysokowydajne procesy na małą skalę mogą produkować substancję leczniczą szybciej niż konwencjonalne linie napełniania i wykańczania mogą ją fiolkować. Oznacza to, że należy zaplanować gromadzenie zapasów substancji leczniczej luzem lub wcześnie zintegrować technologie szybkiego napełniania i wykańczania, aby uniknąć zatorów na dalszych etapach procesu, zapewniając zrównoważenie całego przepływu procesu.

P: Jakie standardy regulują projektowanie i kwalifikację systemów bioreaktorów do produkcji mRNA GMP?

O: Konstrukcja i wykonanie bioreaktora muszą spełniać wymagania higieniczne systemu w zakresie ASME BPE-2022. Ich specyfikacja i weryfikacja powinny być zgodne z podejściem naukowym i opartym na ryzyku, jak określono w dokumencie ASTM E2500-20 w celu zapewnienia przydatności do określonego celu. Co więcej, wspierające media, takie jak systemy wodne, muszą być zgodne z normami takimi jak ISO 22519. Te zintegrowane ramy norm oznaczają, że zespoły inżynieryjne i kwalifikacyjne muszą współpracować od samego początku, aby zapewnić, że system spełnia wszystkie oczekiwania regulacyjne i jakościowe dotyczące sterylnej produkcji biofarmaceutycznej.

Powiązane treści:

- Wymagania dotyczące sprzętu do produkcji szczepionek mRNA: Projekt i specyfikacje specyficzne dla platformy dla COVID-19 i nie tylko

- Kompletny przewodnik po sprzęcie do produkcji szczepionek dla zakładów farmaceutycznych i biotechnologicznych: wydanie 2025 zgodne z GMP

- Filtracja in situ a filtracja wsadowa: Porównanie

- Studium przypadku: 30% Wzrost wydajności dzięki filtracji in situ

- Przetwarzanie wsadowe w izolatorach do testów sterylności

- 5 strategii zwiększania skali systemów filtracji in situ

- Przetwarzanie ciągłe vs. przetwarzanie wsadowe: Optymalizacja operacji EDS

- Usprawnienie odkażania ścieków: Przetwarzanie ciągłe a wsadowe

- BioSafe EDS: Systemy oczyszczania okresowego i ciągłego