Accurately calculating and maintaining the required inward airflow velocity (FPM) in a Biosafety Cabinet (BSC) is a non-negotiable requirement for laboratory safety. Yet, many facility managers and biosafety officers operate under a critical misconception: that meeting a regulatory velocity minimum guarantees effective containment. This assumption is dangerously flawed. True safety depends on a complex interplay of cabinet design, in-situ performance validation, and environmental control. A BSC can pass a certification check under ideal conditions yet fail catastrophically when exposed to routine lab disruptions.

The stakes for getting this right have never been higher. With evolving pathogens and stringent regulatory audits, laboratories must move beyond simple compliance checklists. A miscalculated or poorly maintained airflow velocity directly compromises the Operator Protection Factor (OPF), putting personnel at risk. This guide provides the technical framework to transition from meeting a specification to ensuring a reliable, resilient containment barrier. We will dissect the standards, detail the calculations, and outline the protocols necessary for robust BSL-level protection.

Core BSC Airflow Velocity Standards and Regulations

Understanding the Regulatory Landscape

Regulatory and advisory bodies provide baseline velocity requirements, but these are starting points, not performance guarantees. The California Code, for instance, mandates 75 FPM for Class I and II Type A cabinets and 100 FPM for Type B cabinets. The Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories (BMBL) recommends a velocity greater than 75 FPM. Meanwhile, the primary performance standard, NSF/ANSI 49, specifies that the manufacturer must set the velocity to meet protection criteria. The key insight is that these figures represent minimum compliance thresholds. A cabinet meeting 75 FPM may still fail operator protection tests if its internal aerodynamics are poorly engineered.

The Critical Gap Between Specification and Safety

Relying solely on a velocity specification is a common and critical error. Industry experts emphasize that containment efficacy is fundamentally design-dependent. The inward air curtain must be uniform and stable. I’ve reviewed certification reports where cabinets met the printed spec but showed turbulent or low-velocity zones at the corners of the opening during smoke testing. This validates the principle that compliance is necessary but insufficient for safety. Facility managers must prioritize cabinet selection based on robust, validated design and demand comprehensive in-situ performance testing, not just a numerical velocity check.

Navigating Conflicting Requirements

In practice, laboratories must navigate a hierarchy of requirements. The enforceable rule is often the strictest of local regulation, institutional policy, and the manufacturer’s certified specification. For example, if your local code requires 75 FPM but the cabinet’s NSF/ANSI 49 certification plate specifies 80 FPM, the 80 FPM standard governs. This table clarifies the core standards:

Key Velocity Standards Reference

The following table summarizes the primary airflow velocity standards and their applications, providing a quick reference for compliance planning.

| Cabinet Type / Standard | Minimum Face Velocity (FPM) | Principais considerações |

|---|---|---|

| Class I / II Type A (CA Code) | 75 FPM | Regulatory minimum |

| Type B (CA Code) | 100 FPM | Regulatory minimum |

| NSF/ANSI 49 (General) | Manufacturer-set | Performance specification |

| BMBL Recommendation | >75 FPM | Advisory guideline |

Source: NSF/ANSI 49-2024: Biosafety Cabinetry. This primary standard establishes critical performance criteria, including manufacturer-set airflow velocity requirements, for the design and certification of Class II BSCs. The California Code and BMBL provide complementary regulatory and advisory minimums.

Calculating Average Face Velocity: Methods and Formulas

The Foundational Calculation

The core formula for average face velocity is straightforward: Average Face Velocity (FPM) = Total Volumetric Inflow (CFM) / Area of Work Opening (sq ft). Accuracy hinges on correctly measuring the “Total Volumetric Inflow.” This is not the blower’s output but the actual volume of room air entering the front aperture per minute. Anemometer readings alone are often insufficient for a certified average; they are best for spot checks and troubleshooting.

Method Selection by Cabinet Type

The appropriate measurement technique depends on your BSC’s design and exhaust configuration. For most recirculating cabinets, a calibrated capture hood placed over the work opening provides the most direct and accurate inflow CFM measurement. For hard-ducted Type B cabinets, technicians typically calculate inflow indirectly by measuring the total exhaust flow and subtracting the known downflow supply air volume. Class I cabinets, which have no downflow, require a formal anemometer traverse across a defined grid at the opening.

Mandatory Qualitative Validation

A quantitative velocity calculation is only half the validation. A qualitative smoke test is mandatory to visualize the integrity of the air barrier. This test confirms no spillage under static conditions and during simulated arm movement. Easily overlooked details include ensuring the smoke source does not itself disrupt airflow and checking the entire perimeter of the viewing window. The two methods are complementary; the number verifies the volume, the smoke verifies the curtain.

Measurement Methods Overview

Selecting the correct measurement method is critical for obtaining an accurate average face velocity, as detailed below.

| Tipo de gabinete | Primary Measurement Method | Key Formula Component |

|---|---|---|

| Most Cabinets | Direct capture hood | Total Inflow (CFM) |

| Hard-Ducted Type B | Exhaust flow measurement | Exhaust CFM – Supply CFM |

| Class I Units | Anemometer traverse | Direct grid measurement |

| All Types (Validation) | Qualitative smoke test | Visual barrier confirmation |

Source: Technical documentation and industry specifications.

Performance Validation: How Velocity Relates to BSL Protection

The Operator Protection Factor (OPF) Link

The calculated face velocity directly correlates to the cabinet’s Operator Protection Factor—a measure of how many times safer work is inside the cabinet versus on an open bench. Research underpinning standards like EN 12469:2000 shows that well-designed cabinets can achieve high protection (OPF > 10⁵) at velocities at or above 0.41 m/s (approximately 81 FPM) under ideal, static laboratory conditions. This establishes a foundational performance threshold.

The Fragility of the Air Curtain

The critical vulnerability emerges when ideal conditions vanish. Studies demonstrate that real-world interference—a 0.5 m/s cross-draft, rapid arm movement, or a person walking by—can degrade the OPF by over 1000-fold. This performance loss varies dramatically between cabinet models. Some designs maintain a robust barrier with minor disruption; others spill almost immediately. This evidence validates the need for a performance buffer. Your target velocity should account for your specific lab environment.

Establishing a Velocity Buffer

For BSL-2 and BSL-3 work, the decision is to set the operational velocity toward the higher end of the acceptable range. Instead of targeting the bare minimum of 75 FPM (0.38 m/s), consider a setpoint of 0.5 to 0.55 m/s (100-108 FPM) where possible, provided it does not disrupt sensitive work or exceed manufacturer limits. This buffer enhances resilience against inevitable environmental disruptions. It is a practical risk-mitigation strategy, not just theoretical safety.

Velocity and Protection Correlation

This table illustrates the relationship between face velocity and operator protection, highlighting the impact of real-world conditions.

| Velocidade da face | Operator Protection Factor (OPF) | Real-World Condition |

|---|---|---|

| ≥ 0.41 m/s (81 FPM) | > 10⁵ | Ideal, static lab |

| Below setpoint | Predictable degradation | Undisturbed environment |

| With interference | >1000-fold reduction | Cross-drafts, movement |

| BSL-2/3 Recommended | 0.5-0.55 m/s | Buffer for resilience |

Source: EN 12469:2000 Biotechnology — Performance criteria for microbiological safety cabinets. This standard defines fundamental performance criteria for MSCs/BSCs, including inward airflow velocity for operator protection, which forms the basis for establishing protective velocity setpoints and understanding performance thresholds.

Practical Implementation and Environmental Considerations

The Certification Imperative

Post-installation and annual certification by a qualified professional are non-negotiable operational costs, not optional compliance activities. This certification must include quantitative velocity measurement, HEPA filter integrity testing (DOP/PAO challenge), and smoke pattern visualization. The velocity should be set to meet the stricter of the manufacturer’s specification or the regulatory minimum. Maintain these records for a minimum of five years for audit compliance and performance trend analysis.

Strategic Siting as a Force Multiplier

The cabinet’s location is a primary determinant of its reliability. Place BSCs away from doors, high-traffic aisles, and room supply air vents. A cross-draft of just 0.25 m/s (50 FPM) can destabilize the inflow air curtain. According to guidance in standards like BS 5726:2005, a distance of at least 1 meter from traffic lanes and other airflow sources is a prudent minimum. The laboratory environment itself acts as a secondary containment layer; a well-controlled, low-turbulence room supports primary device reliability.

Implementing a Proactive Monitoring Protocol

Beyond annual certification, implement simple operator-led pre-use checks. These include a visual inspection of the magnehelic gauge (if present) for pressure drop and a brief smoke test at the opening edges. Training staff to recognize the sound of a balanced cabinet and to report any changes is a low-cost, high-impact practice. This frontline monitoring creates an early warning system for performance drift.

Implementation and Siting Requirements

A successful BSC program depends on strict adherence to certification, siting, and documentation protocols, as outlined here.

| Requisito | Frequency / Specification | Critical Action |

|---|---|---|

| Certificação BSC | After installation, relocation | Mandatory validation |

| Certificação anual | Every year | Non-negotiable operational cost |

| Velocity Setpoint | Stricter of: manufacturer or regulation | Compliance and safety |

| Strategic Siting | Away from doors, vents, traffic | Minimizes airflow interference |

| Record Retention | Mínimo de 5 anos | Compliance, trend analysis |

Source: BS 5726:2005 Microbiological safety cabinets. Information to be supplied by the purchaser to the vendor and to the installer, and siting and use of cabinets. This standard provides crucial guidance on the siting, installation, and use of cabinets to ensure they operate correctly, directly informing certification frequency and strategic placement requirements.

Addressing Common Airflow Interference and Disruption

Identifying Sources of Interference

Mitigation starts with identification. Common disruptors include HVAC supply diffusers, open windows, lab doors opening/closing, pedestrian traffic, and heat sources near the cabinet. Even adjacent equipment like centrifuges or incubators can create thermal plumes that disrupt airflow. A formal room airflow assessment, often using smoke tubes, should be part of the initial siting process and repeated after any significant lab renovations.

Operational Protocols to Minimize Risk

Laboratory SOPs must address movement. Techniques include minimizing rapid arm motions, avoiding passing materials over the top of the opening, and not overcrowding the work surface. Staff should work from clean to dirty within the cabinet, moving items slowly. Training must contextualize these practices—not as arbitrary rules, but as essential actions to preserve the integrity of the invisible protective air curtain they rely on.

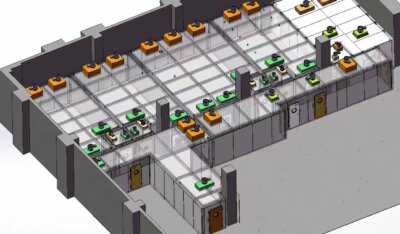

The Layered Defense Strategy

While the BSC is the primary containment, a holistic biosafety architecture employs layered defenses. This means ensuring the laboratory itself has sealed walls, directional airflow, and HEPA-filtered exhaust where required. This secondary containment layer mitigates the consequence of a momentary airflow breach at the cabinet. Investing in a well-designed lab environment supports and protects your investment in primary containment devices.

Advanced Considerations for BSL-3 and BSL-4 Containment

BSL-3: Enhanced Primary Barriers

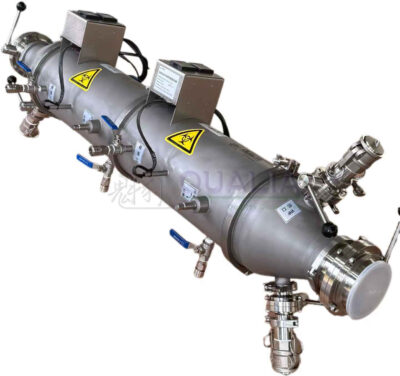

For BSL-3 work, especially with volatile chemicals or radionuclides, ducted Type B2 BSCs (requiring a minimum of 100 FPM inward velocity) are standard. These cabinets offer total exhaust of all inflow and downflow air, providing both biological and chemical containment. The margin for error is smaller; thus, certification frequency, environmental control, and operator proficiency requirements are exponentially higher.

BSL-4: The Shift to Absolute Containment

At BSL-4, the paradigm shifts from an air curtain to a physical barrier. Class III gloveboxes or positive-pressure suits with Class I or II BSCs are used. Here, the concept of “face velocity” is irrelevant for the primary barrier; the isolator is sealed. The supporting laboratory suite is a highly engineered, airtight environment with complex ventilation controls.

Re-Evaluating Design Dogma

An emerging insight from modern BSL-4 design challenges historical norms. Evidence suggests that in today’s airtight suites constructed to ISO 14644-7 standards, maintaining intricate room-to-room pressure cascades may add negligible safety benefit where air leakage is minimal. This points toward an evidence-based approach where facility design is simplified based on actual risk assessment, though the primary barrier itself remains subject to flawless performance and rigorous verification.

High-Containment Primary Barriers

The choice of primary containment device escalates with biosafety level, as shown in this comparison.

| Nível de contenção | Typical Primary Barrier | Minimum Face Velocity (Typical) |

|---|---|---|

| BSL-3 (Volatile Agents) | Ducted Type B2 BSC | 100 FPM |

| BSL-4 | Class III Glovebox / Isolator | Sealed, no face velocity |

| Modern BSL-4 Suite | Airtight room design | Simplified pressure gradients |

Observação: BSL-4 primary containment is a sealed physical barrier, not an air curtain.

Source: ISO 14644-7:2004 Cleanrooms and associated controlled environments — Part 7: Separative devices. This standard specifies requirements for separative devices like isolators and clean air hoods, providing the foundational framework for the sealed, pressurized containment strategies used in high-level biosafety labs.

Establishing a Robust BSC Maintenance and Certification Protocol

The Core Certification Elements

A defensible protocol mandates annual certification by an accredited professional. The core tests are non-negotiable: quantitative face velocity measurement, downflow velocity measurement, HEPA filter integrity testing via a polydisperse aerosol challenge (DOP/PAO), and a qualitative smoke test for airflow pattern. This suite of tests validates both the numerical performance and the functional integrity of the containment system.

Operator Responsibilities and Pre-Use Checks

Between professional certifications, the operator is the first line of defense. A simple pre-use checklist should include verifying the cabinet is on and the alarm is not activated, checking the gauge readings against baseline levels, and performing a brief smoke test at the opening. Any anomaly must trigger a work stoppage and a call for service. This culture of personal accountability is critical for continuous safety.

Decommissioning and Total Cost Analysis

The protocol must define clear decommissioning triggers: failed filter test, irreparable airflow imbalance, or physical damage. This decision intersects with total cost of ownership. For applications not requiring product protection (e.g., handling waste containers), the robust simplicity of a Class I cabinet often presents a more predictable and cost-effective solution over its lifecycle, with easier verification and maintenance compared to complex Class II units.

Maintenance Protocol Framework

A comprehensive maintenance and certification protocol assigns specific tasks to qualified personnel, ensuring ongoing safety.

| Elemento de protocolo | Test / Check | Realizado por |

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative Validation | Face velocity measurement | Profissional certificado |

| Teste de integridade do filtro | Desafio DOP/PAO | Profissional certificado |

| Qualitative Validation | Smoke pattern visualization | Profissional certificado |

| Verificação operacional | Pre-use visual/functional | BSC operator |

| Decommissioning Trigger | Suspect performance | Immediate action |

Source: NSF/ANSI 49-2024: Biosafety Cabinetry. The standard mandates the specific quantitative and qualitative tests required for field certification, forming the core of a rigorous maintenance protocol to ensure ongoing cabinet performance and safety.

Effective BSC airflow management requires moving from passive compliance to active performance assurance. First, know and apply the correct standard—defaulting to 75 FPM for Type A and 100 FPM for Type B cabinets, unless stricter specifications govern. Second, validate performance in situ with both quantitative and qualitative tests, recognizing that a certification sticker does not guarantee real-world safety. Third, control the laboratory environment through strategic siting and rigorous staff training to mitigate disruptive interference.

Need professional guidance to audit your biosafety cabinet protocols or design a resilient containment strategy? The experts at QUALIA specialize in translating complex standards into actionable, safe laboratory operations. We provide the technical depth to ensure your primary engineering controls perform as your first and most reliable defense. For a detailed consultation on your specific containment challenges, you can also Entre em contato conosco.

Perguntas frequentes

Q: What are the minimum inward airflow velocity requirements for different BSC types?

A: Regulatory minimums are 75 feet per minute (FPM) for Class I and Class II Type A cabinets, and 100 FPM for Type B cabinets, as seen in standards like the California Code. However, these are baseline compliance figures, not performance guarantees. For projects where operator safety is paramount, you must verify the stricter of the manufacturer’s specification or the local regulatory minimum during certification.

Q: How do you accurately calculate the average face velocity for certification?

A: You calculate average face velocity by dividing the cabinet’s total volumetric inflow (in CFM) by the area of its work opening in square feet. The method to obtain the inflow CFM varies by cabinet type, using a capture hood, exhaust flow calculation, or direct anemometer traverse. This means facilities must ensure their certification provider uses the correct measurement technique specified in standards like NSF/ANSI 49-2024 for their specific BSC model.

Q: Why is meeting the minimum FPM standard insufficient for guaranteed operator protection?

A: A cabinet can pass a velocity check yet fail operator protection tests if its internal aerodynamic design is poor. Real-world performance depends on robust engineering, not just a numeric threshold. This means your procurement and validation process must prioritize in-situ performance testing under dynamic conditions over simple specification compliance to ensure actual safety.

Q: How should we set BSC velocity to account for real-world lab disruptions?

A: Set operational velocities toward the higher end of standard ranges, such as 0.5-0.55 m/s (approx. 100-108 FPM), to build a performance buffer. Research shows cross-drafts and movement can degrade containment effectiveness by over 1000-fold. If your BSL-2 or BSL-3 lab has high traffic or variable HVAC currents, plan for this higher setpoint during annual certification to mitigate interference risks.

Q: What is the critical protocol for maintaining BSC performance over time?

A: Implement a mandatory annual certification by an accredited professional, including quantitative face velocity measurement, HEPA filter integrity testing, and qualitative smoke pattern visualization. This recurring validation is a fixed operational cost, not an optional activity. Facilities must budget for this sensitive maintenance and retain all records for at least five years to demonstrate compliance and track performance trends.

Q: When selecting a BSC, how does cabinet class impact long-term operational costs?

A: The total cost of ownership for complex Class II cabinets includes high recurring expenses for sensitive annual certification. For applications not requiring product protection, the simpler design of Class I cabinets offers more predictable performance degradation and easier verification. This means operations focused solely on personnel and environmental protection should conduct a cost-benefit analysis that includes these long-term maintenance realities.

Q: What are the advanced containment considerations for BSL-3 and BSL-4 laboratories?

A: BSL-3 often requires hard-ducted Type B2 cabinets (100 FPM minimum), while BSL-4 uses Class III gloveboxes or isolators. A key insight for modern suites is that complex room pressure cascades may add minimal safety in airtight environments. For projects designing or upgrading high-containment spaces, this challenges historical dogma and suggests focusing resources on flawless primary barrier performance and evidence-based risk assessment.

Conteúdo relacionado:

- Cabines de segurança biológica Classe II Tipo B2: Exaustão total

- Cabines de segurança biológica Classe I: Características e usos

- Teste de fluxo de ar para gabinetes de biossegurança: Principais verificações

- Biological Safety Cabinet Selection for BSL 2/3/4 Labs: Class I, II, III Comparison & NSF/ANSI 49 Compliance Requirements

- Instalação da cabine de biossegurança: O que você precisa saber

- Class III Biosafety Cabinet vs Class II BSC: 12 Critical Differences for BSL-3 and BSL-4 Containment Selection

- Explicação sobre as cabines de segurança biológica Classe II Tipo A2

- Isoladores de biossegurança Classe III: Proteção máxima

- Class III vs Class II Biosafety Cabinet Airflow Performance: CFM and Containment Data Comparison